Sometimes, in what’s a near-endless proliferation of advanced metrics and tools across baseball, it feels like it’s all spreadsheet talk, that some of these terms exist only in the realm of analysts. Then you listen to the players themselves, and you realize that’s not true at all. Across the sport, players are using data and technology to improve their own games.

All you have to do is just listen to them tell you about it. In this case, it's hitters, working on their swings.

“It’s been all about bat path,” Boston breakout rookie Kristian Campbell, the April American League Rookie of the Month, said to FanGraphs this spring. “Instead of being flat, or straight down, I’m trying to hit the ball at a good angle.”

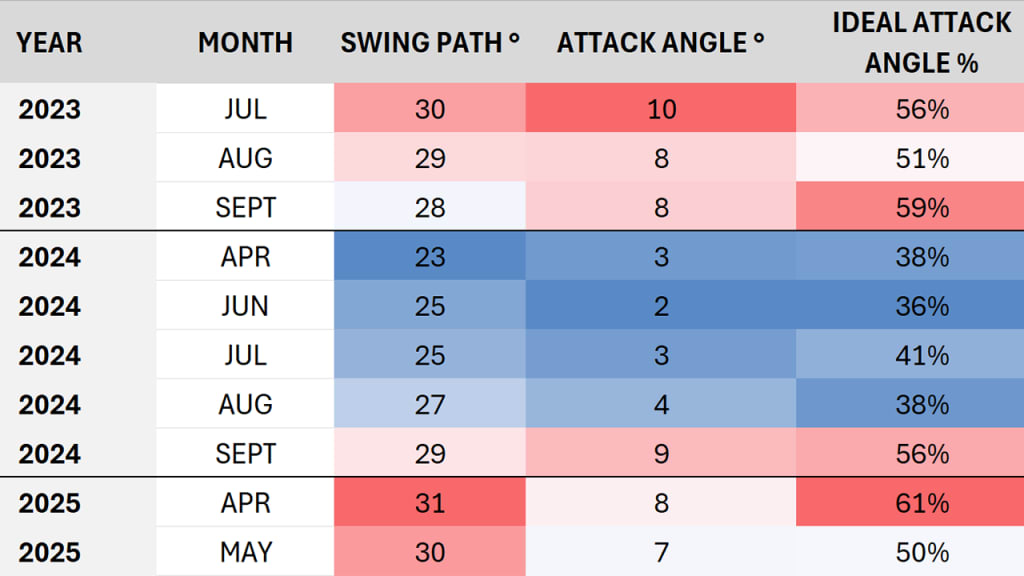

“[I was] making sure that my attack angle was on a more matching plane,” explained Arizona star Corbin Carroll to MLB.com's David Adler earlier this month, when asked about the midseason changes he made last year that turned his initially disappointing campaign around. “Making that window of quality contact a little bit bigger, by bettering my bat path. And so yeah, I think it's a combination of it -- some attack angle, and also having my vertical bat angle a little bit lower [i.e. steeper] as well. A combination of those two was what I focused on.”

Good to know. Carroll’s attack angle was in the 25th percentile of the "ideal" range before the break last year, as he struggled with a .213 first-half average. In 2025, as he makes noise in the NL MVP race, it’s in the 100th percentile, i.e., it is the best.

If this sounds confusing, it is. We're here to explain it -- and, as always, if there’s a seemingly futuristic way of thinking about hitting, then Ted Williams thought about it long ago.

“I advocate a slight upswing (from level to about 10 degrees), Williams wrote in “The Science of Hitting.” Our numbers are slightly different, but that was him thinking about angles and degrees in 1971 – well before any current player was born. Even Rich Hill.

It’s 2025 now, and only now are we able to share publicly some of the things those stars have been thinking about. After last year’s release on Baseball Savant of bat speed, squared up rate, blasts, swing length and swords, and this spring’s look at batter positioning and intercept points, let’s talk about how the bats actually move, with four new metrics – swing path, attack angle, ideal attack angle and attack direction.

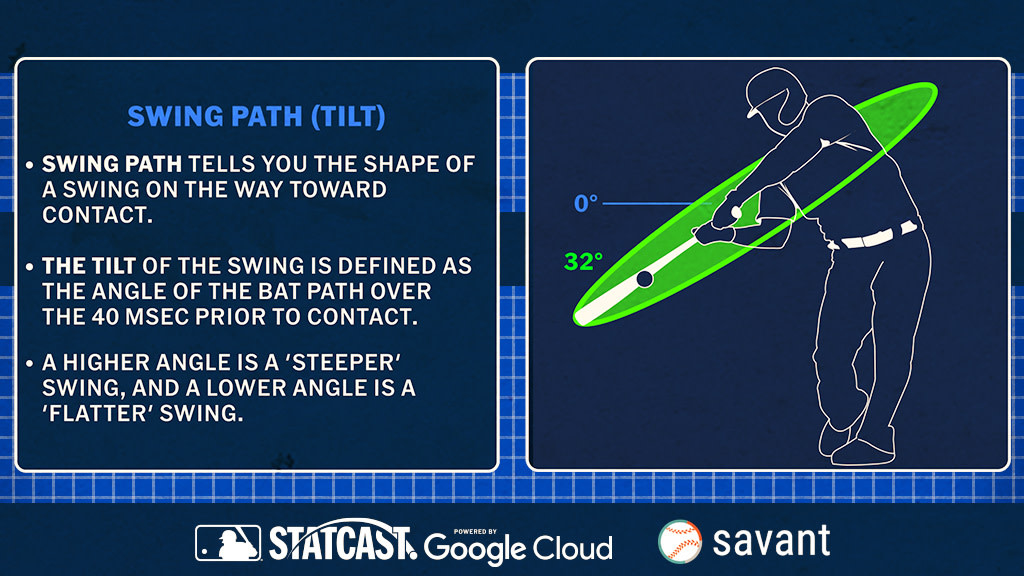

It looks like this:

Here’s what it all means. It's all available at Baseball Savant.

1) SWING PATH (TILT)

What is it? It’s the swing’s shape. This is the one you want if you’re looking for uppercuts, or flat swings, or anything in between. Is a hitter getting too steep? Flattening out? Look here.

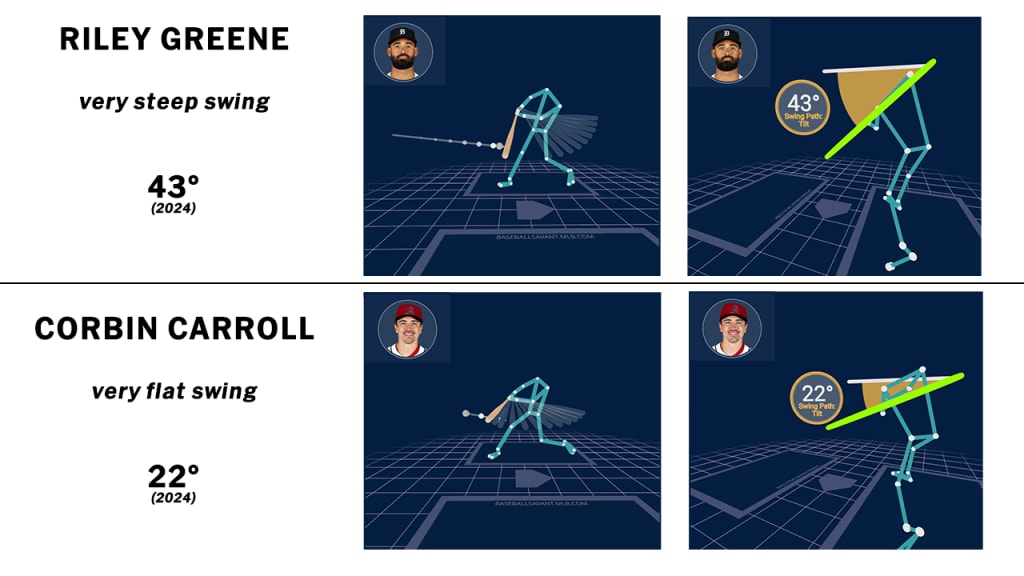

It’s defined by taking the angle of the bat path in the last 40 milliseconds prior to contact – the shape, basically, on the way to the ball. The bigger the number, the steeper the swing. While the Major League average is 32°, the range here for seasonal averages goes from something like 20° at the flattest all the way to near 50° at the steepest.

The steepest swings in 2025

- 46° Riley Greene

- 42° Freddie Freeman

- 41° Drew Waters

- 41° Andy Pages

- 40° James Wood

- 40° Spencer Torkelson

The flattest swings in 2025

- 23° Anthony Santander (LH only)

- 24° Jake Burger

- 24° Alejandro Kirk

- 24° Yandy Diaz

That’s right: near 20° is the flattest swing, not 0°. No one’s actually swinging at 0°, or perfectly flat to the ground – the blue line in the image above – because with the ball coming on a downward angle, “matching the plane” requires at least some kind of upward-angled swing. It’s more meaning that it’s on plane with the pitch coming in, which of course is entering the zone at a slight downward angle, due to gravity and the simple factor of a pitcher who might be more than six feet tall, standing on a 10-inch mound, releasing the ball from perhaps over his head.

The difference is pretty clear to see if you look at one of 2024’s flattest swings, the 22° of Carroll, compared with Riley Greene’s massive 43° uppercut.

It's useful if you consider the case of Mets catcher Francisco Alvarez, who had a good-not-great 2024 (101 OPS+), then spent the winter talking about how he planned to revamp his mechanics, working with J.D. Martinez to do so. ("I had to fix my swing," Alvarez said,” after a year in which his home run output dipped from 25 to 11.)

Last April, he was one of the flattest swingers in baseball, with a 23° swing path. This year, he’s pretty close to league average. It’s not, as you’ll see, a 1:1 correlation between “good production” or “bad production.” But in terms of whether you can see if a player is changing his swing after he talks about doing exactly that: You sure can.

On an individual swing, this is heavily influenced by pitch location, of course. Last year, if you split pitch locations by low, middle and high, you’ll see that the swing path went from 37° (low pitches) to 32° (middle) to 25° (high), which makes intuitive sense. The lower the pitch is, the lower you’re going to have to dig to get to it. If it’s higher, you’re not out there with a steep, uppercut swing. You can’t be.

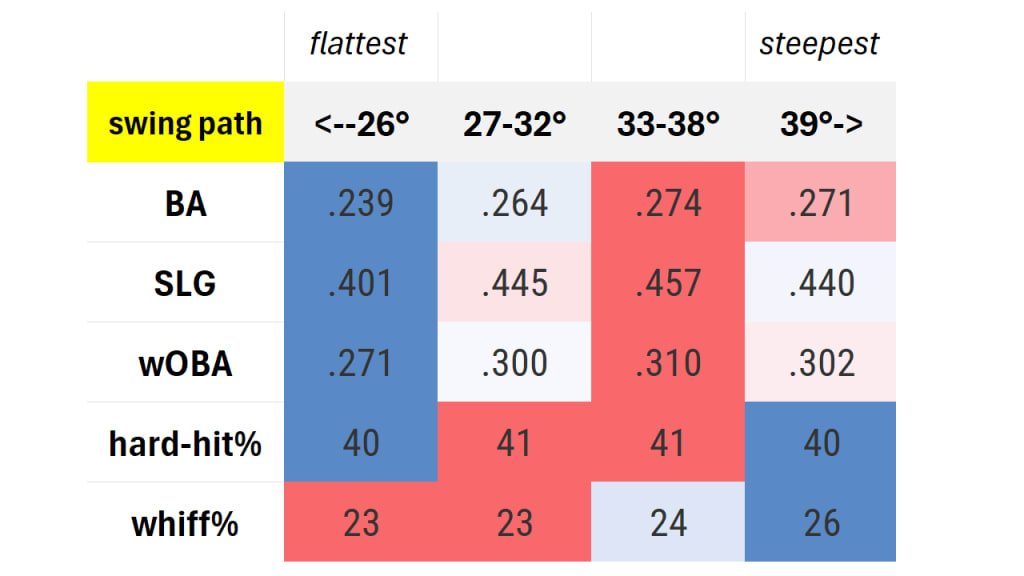

Why does it matter? This is more of a stylistic thing, really. Unlike a lot of other things, it’s not as simple as “more is good” or “less is bad.” It tells you something about the type of swinger you’re seeing, and lets you try to better understand swing changes as players talk about them.

Still, there are some correlations between swing paths and outcomes. Too flat, you’re not going to get much power. Too steep, you’re going to make less contact. Right in the middle, you’ll be happy. (Goldilocks, it turns out, might have been an impactful batter.) This is, for the most part, exactly as you’d expect.

Who’s interesting? Greene and Freddie Freeman have the biggest uppercuts, in the 46° range. That’s consistent; in the three seasons of tracking, they combine for the top six uppercuttiest slots among qualified hitters. Aaron Judge used to be there, too, up at 42° in 2023 – though he’s cut it down to 39° this year.

The surprising name for the flattest regular swing, one that’s stayed at 24° each season? Jake Burger, who may have had a consistent swing path yet with performance that is anything but; after hitting 29 homers for Miami last year, he found himself in Triple-A for parts of 2025. Whatever his issues are, it’s not this.

Has anyone changed in 2025? We always like to see who’s doing something that’s different, right? The biggest gainers in swing path – meaning those who have made their swing less flat – are Spencer Torkelson (+7°, from 33° to 40°), Zach Neto (+5°), Wyatt Langford (+4°), and Carroll (+3°) which is interesting as all are having breakout seasons. Of course, Marcus Semien is +3° as well, and he's off to a career-worst start.

The other side is interesting as well, because no one has flattened their path more than Jorge Polanco as a lefty (down 7°, from 38° to 31°) – and he’s having a spectacular season. Joc Pederson, at -3° from last year, has not. It’s a good reminder that this isn’t about good or bad; it’s about what works for you. It’s mostly about not being too extreme in either direction.

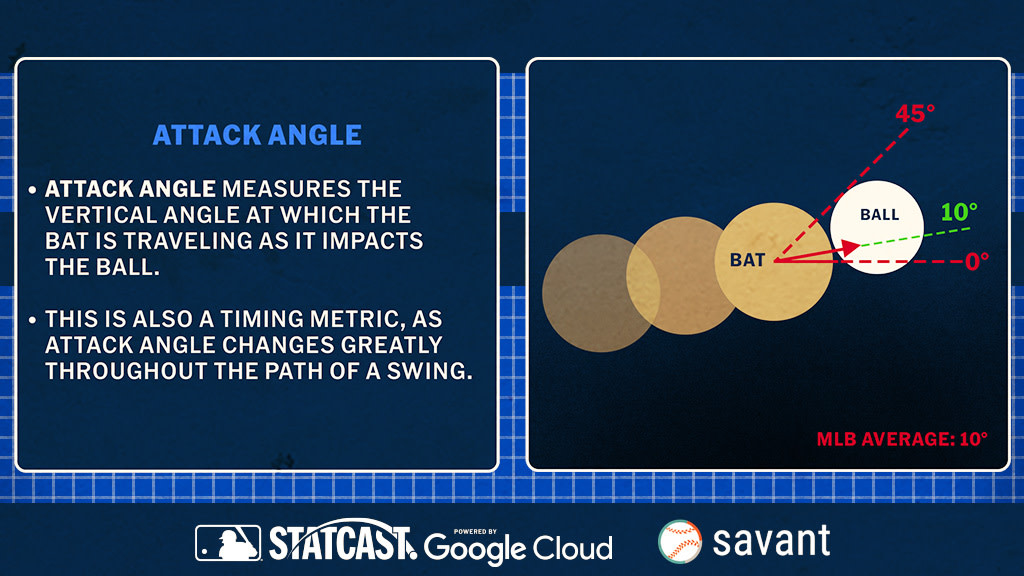

2) ATTACK ANGLE

What is it: If swing path is telling you about the shape of the bat path on the way toward contact, then attack angle is telling you what’s happening with the bat at contact – at what vertical angle the bat is moving as it impacts the ball (or comes closest to doing so, on misses). Here, 0° would be perfectly flat, with positive numbers showing a bat moving upward and negative giving you a bat moving downward.

Attack angle is the bat’s angle at impact. Launch angle is the ball’s angle at impact. There can be overlap, but they’re different numbers for different things.

There’s one particular part of that sentence which is doing a whole lot of work: at impact.

What that means is that this is, among other things, a timing metric. Go back and look at a swing video, this time of Pete Alonso, and focus on that red arrow on the bat. Look at how drastically it moves as the swing progresses. You might get dozens of attack angles during the swing – 4 degrees per frame, per MLB.com’s Tom Tango – and the one that matters is the one that happens at contact. That means that having an undesirable attack angle might be about being early or late, as well as the way you’re moving your bat.

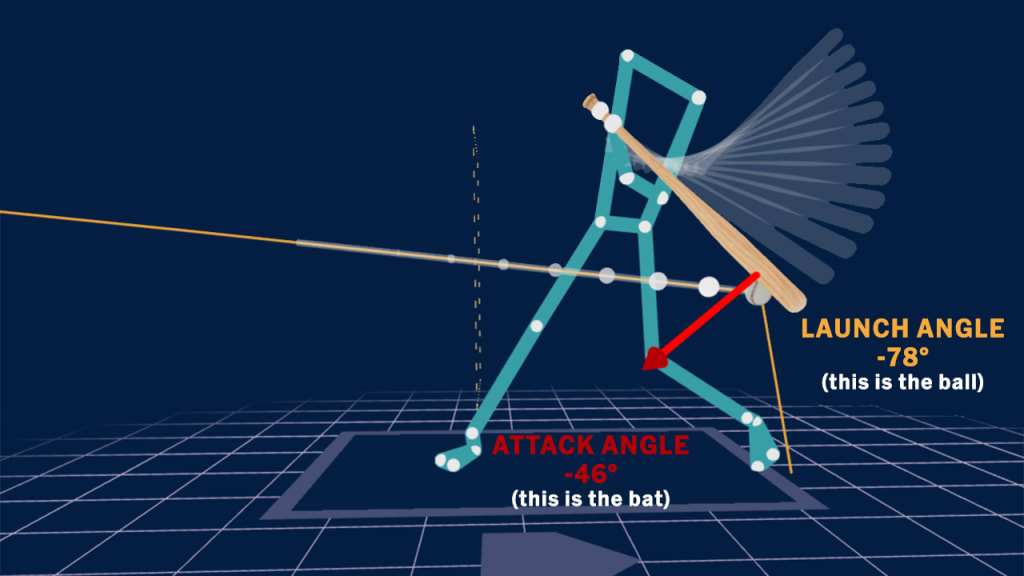

Or, why did James Wood have an attack angle of -46° on this ball he pounded directly into the dirt? It’s not because he was swinging down. It’s because he was massively late, catching the ball well behind him. Were he on time, then surely the attack angle would have been more favorable.

For this, there’s going to be a lot of overlap with whether you’re hitting the ball in the air or not. While the average attack angle is 10°, you’ll find some extreme fly ball guys at the top end (Tyler O’Neill, Eugenio Suárez and Nolan Gorman are all in that 20° range), and guys who live on the ground at the lower end (Milwaukee teammates Joey Ortiz and Brice Turang down around 1°). Why doesn’t Vladimir Guerrero Jr. hit as many homers as you’d think, given his excellent exit velocities? Look to the fact that his 1° attack angle is essentially the lowest in the game.

As with swing path, it’s very sensitive to pitch location – low pitches see an average attack angle of 16°, middle 9° and high 7°.

Why does it matter? It matters because hitters are aware of it and speak directly about it, for one thing. If it matters to them, it matters to us. But, again, this is not a case of “more is better.” You can have too high of an attack angle, and too low as well.

That's why there is a happy middle you want to be in -- that "ideal" range between 5° and 20°-- that we'll explain further shortly.

Who’s interesting? Freddie Freeman, for one.

Earlier this month, the Los Angeles Times reported that after a late-July single off Paul Skenes, "that's what Freeman now cites as the origin point for one of the most productive stretches of his entire career -- the moment when, after more than a year of sensing his mechanics at the plate were slightly off, his simple swing finally felt once again on-line and in-sync."

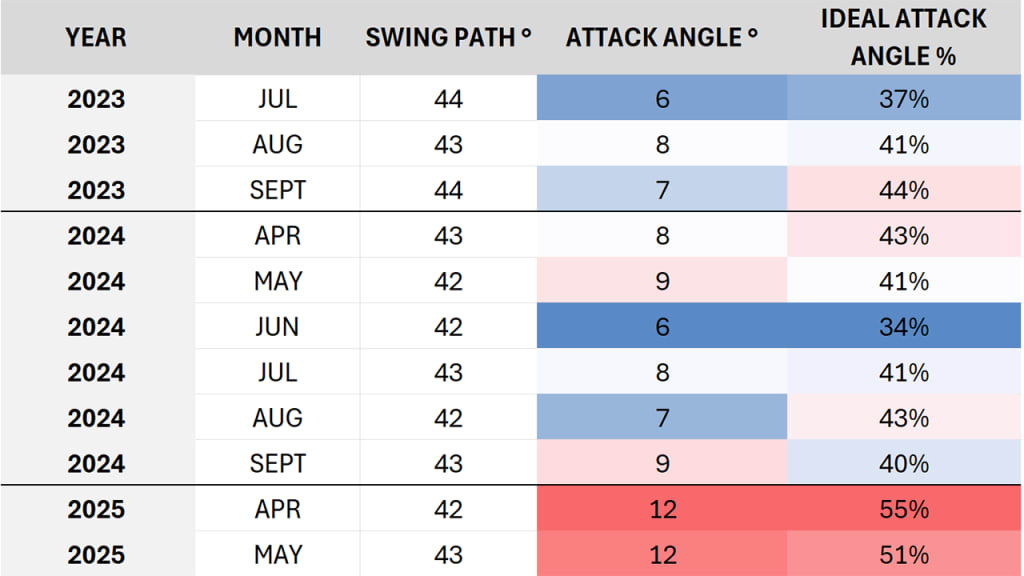

It's pretty easy to see. It's not so much that the swing path -- the shape of the generally uppercut swing -- changed. It's that the vertical angle that the bat was moving at the moment of contact did. It means his timing has changed -- on-line and in-sync, you might say.

Freeman, at 35, is off to one of the best starts of his likely Hall of Fame career.

Has anyone changed in 2025? Langford, Ryan McMahon, Torkelson and Freeman have all increased that attack angle significantly. So has Carroll. There's a lot more good than bad there, though Brendan Rodgers and McMahon haven't exactly been productive. It might be that this is yet another thing that Coors Field messes with. It might be that there's a lot more to hitting, at all times, than can be boiled down into one number.

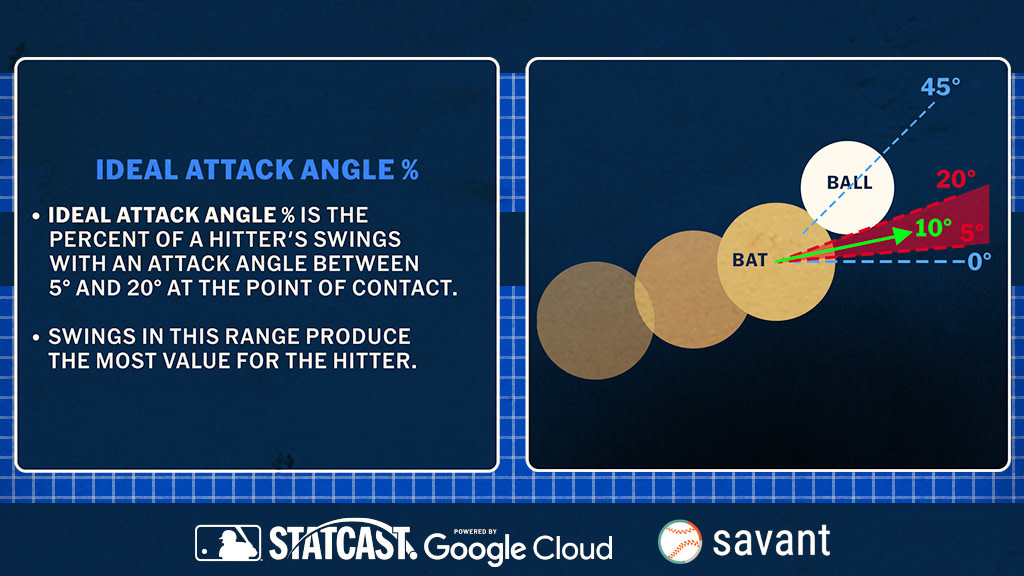

3) IDEAL ATTACK ANGLE

What is it? A way to put attack angle numbers into context. It’s hard to understand if, say, a 15° attack angle means anything. It’s a lot easier to understand if you know what’s valuable – in the same way that you might look at hard-hit rate (batted balls over 95 mph) to get an idea of what’s good exit velocity.

Fortunately for us, this ends up being approximately 50% of swings per season. It’s also roughly exactly the angle at which pitches enter the hitting zone – on a downslope between -5 and -20°. When hitters talk about “keeping the bat in the zone longer,” they don’t mean moving the bat slowly. They mean matching their attack angle to the plane of the pitch, or what Williams was talking about when he wrote “A slight upswing … puts the bat flush in line with the path of the ball for a longer period.”

Why does it matter? The numbers since the 2023 All-Star Game say it all.

Ideal attack angle swings (between 5° and 20°)

- .272 AVG / .487 SLG / .323 wOBA

All other attack angle swings

- .250 AVG / .354 SLG / .261 wOBA

Who’s interesting? Well, the top of the list is full of fascinating names ... and some less interesting ones, too.

Best ideal attack angle rate, 2025

- 74% Ketel Marte (as a LH)

- 74% Corbin Carroll

- 72% Kyle Schwarber

- 72% Brenton Doyle

- 71% Miguel Vargas

- 69% Carlos Santana (as a RH)

- 68% Alex Bregman

- 68% Juan Soto

- 68% Luis García Jr.

There’s a number of great hitters here – surely, seeing Marte, Carroll, Schwarber, Bregman and Soto makes plenty of sense. If the presence of Vargas and Doyle surprise, we’d mostly agree -- although it's worth pointing out that Vargas has been on fire for the last month, hitting .333/.404/.609 in his last 99 plate appearances, after making some notable mechanical changes.

Has anyone changed in 2025? We’re not displeased to see Carroll making the largest improvement here, from 53% to 74%, that's for sure.

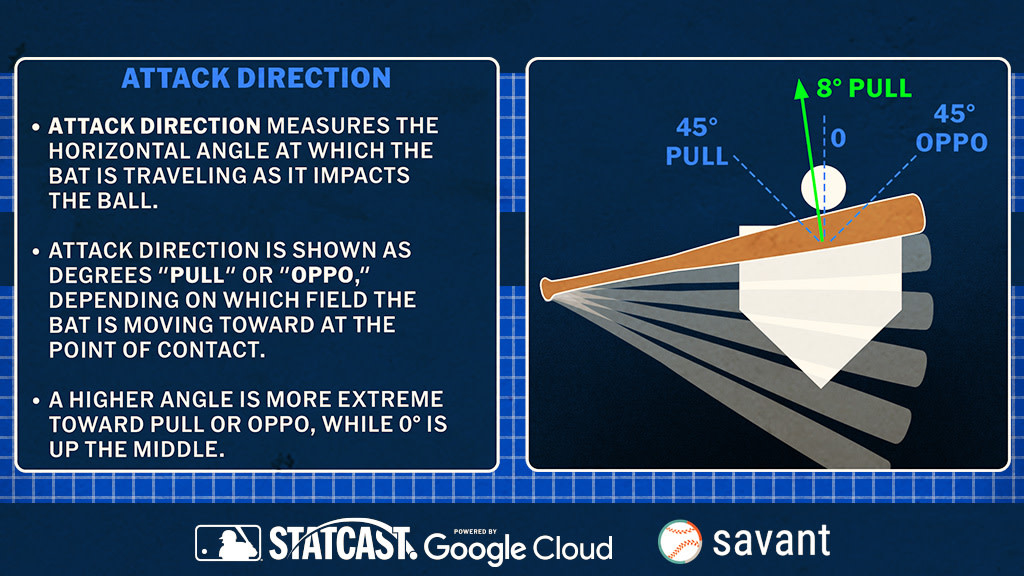

4) ATTACK DIRECTION

What is it? The same thing as attack angle, just from the horizontal point of view. Like with attack angle, it tells you about timing, because it’s about the angle of the bat at the point of contact. If you’re late, you can’t possibly have a pull-angled attack direction, right? A 0° attack direction would be a neutral one, though the average is slightly angled to the pull side, at 2°.

This is also sensitive to pitch height, though not for exactly the reason you’d think – it’s because you’re more likely to see velocity high and breaking or offspeed low.

The most pull-oriented swings in 2025

- 15° Isaac Paredes

- 14° JJ Bleday

- 11° Nolan Arenado

- 11° Matt Mervis

- 11° Bo Naylor

The most oppo-oriented swings in 2025

- 11° Brice Turang

- 8° Rafael Devers

- 8° Gabriel Moreno

- 8° Nathaniel Lowe

- 7° Jackson Holliday

- 7° Christian Yelich

- 7° William Contreras

You couldn't possibly be surprised to find pull-power-only notables like Paredes and Arenado there, right?

This, again, is more of a descriptor of hitting style than it is about "being good or bad," though you'll be unsurprised to learn that pull-side hitters have an advantage in power (approximately 120 points of slugging, splitting pull and oppo at the 0° mark).

There's plenty more to come -- think things like which pitches miss bats by the most, and which fastballs make batters the latest. For now, all of the newest toys are available at Baseball Savant.