Ichiro has left a lasting impact on baseball -- and he's far from finished

Shohei Ohtani is considered by many to be the best baseball player in the world today.

The two-way superstar is the headliner on a long list of Japanese players who successfully made the transition from Nippon Professional Baseball to MLB over the past 20-plus years. Others include Hideki Matsui, Daisuke Matsuzaka, Masahiro Tanaka and contemporary stars Yu Darvish, Seiya Suzuki, Kodai Senga, Yoshinobu Yamamoto and Shota Imanaga.

But at the turn of the century, the notion that a player from NPB would become the greatest player on the planet would have seemed preposterous to many in the baseball world. Japanese baseball, though more than 125 years old at the time, was widely viewed as vastly inferior to baseball in North America.

And besides, not a single position player had ever made the transition from NPB to MLB.

Then emerged on the scene a diminutive outfielder who upended the game with a peerless combination of artistry, precision and flair in an era dominated by brute strength and record-breaking power.

He changed the landscape of the game on two continents, bridging 5,000 miles of ocean between them with a throwback brand of baseball that thrilled fans and utterly flummoxed the opposition.

His impact on Japanese baseball and its export to the West -- and even on Japan as a whole -- cannot be overstated.

As he prepares to become the first Japanese-born player to be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame this weekend, an appreciation is in order not only for his greatness as a baseball player, but also for the profound ways in which this individual transformed our perceptions and inspired millions around the world to dream big.

What follows is a look back at the paradigm-shifting move he made from the Far East to the West a quarter century ago, highlighting the exploits of a ballplayer so good you don’t even need to say his full name for MLB fans to know exactly who you’re talking about. All they need to hear is:

“Ichiro.”

The Right Man at the Right Time

“Not by any means was that a goal of mine, to come over and prove what Japanese baseball players can do,” Ichiro said through interpreter Allen Turner. “It was the right timing for me to come over, and I wanted to take on the challenge.”

After winning seven consecutive NPB batting titles with the Orix Blue Wave, among numerous other accomplishments, there was nothing left for the outfielder to chase in Japan.

This wasn’t a situation in which an individual was hand-picked to be the first NPB position player to sign with an MLB club, but the marriage of man and moment was serendipitous.

“He was the right person to be the first position player to come over,” said Brad Lefton, a bilingual journalist based in St. Louis who has covered baseball in Japan and America for more than 30 years. “The way he approaches things, he has an ability to think through things like nobody else. And he could prepare for things like nobody else.

“You saw that in the way that he was instantly successful. That was in part due to all of the thought he put into what he needed to do to hit the ground running. Because there was no example.”

Not only was there no example to follow, there were a lot of doubters along the path -- on both ends.

“I think Japanese baseball always had an inferiority complex,” Lefton said. “Just not being able to imagine that players from there could compete here.

“And it was probably the same on this side, too -- you had individuals like Bobby Valentine and Tommy Lasorda who had been there and knew that there was talent that could play here, but having individuals know it and having the whole game accept it are two different things.”

So even though Ichiro’s focus was always on what he was doing -- not on the impression it made on the world around him -- it wasn’t lost on him what his signing with the Mariners in November 2000 meant. And looking back now, he sees how far Japanese baseball has come.

“I think, unfortunately, back in those days, Japanese baseball wasn’t looked upon very highly,” Ichiro said. “And I think maybe that’s changed a little bit.”

The moment it began to change came on April 11, 2001.

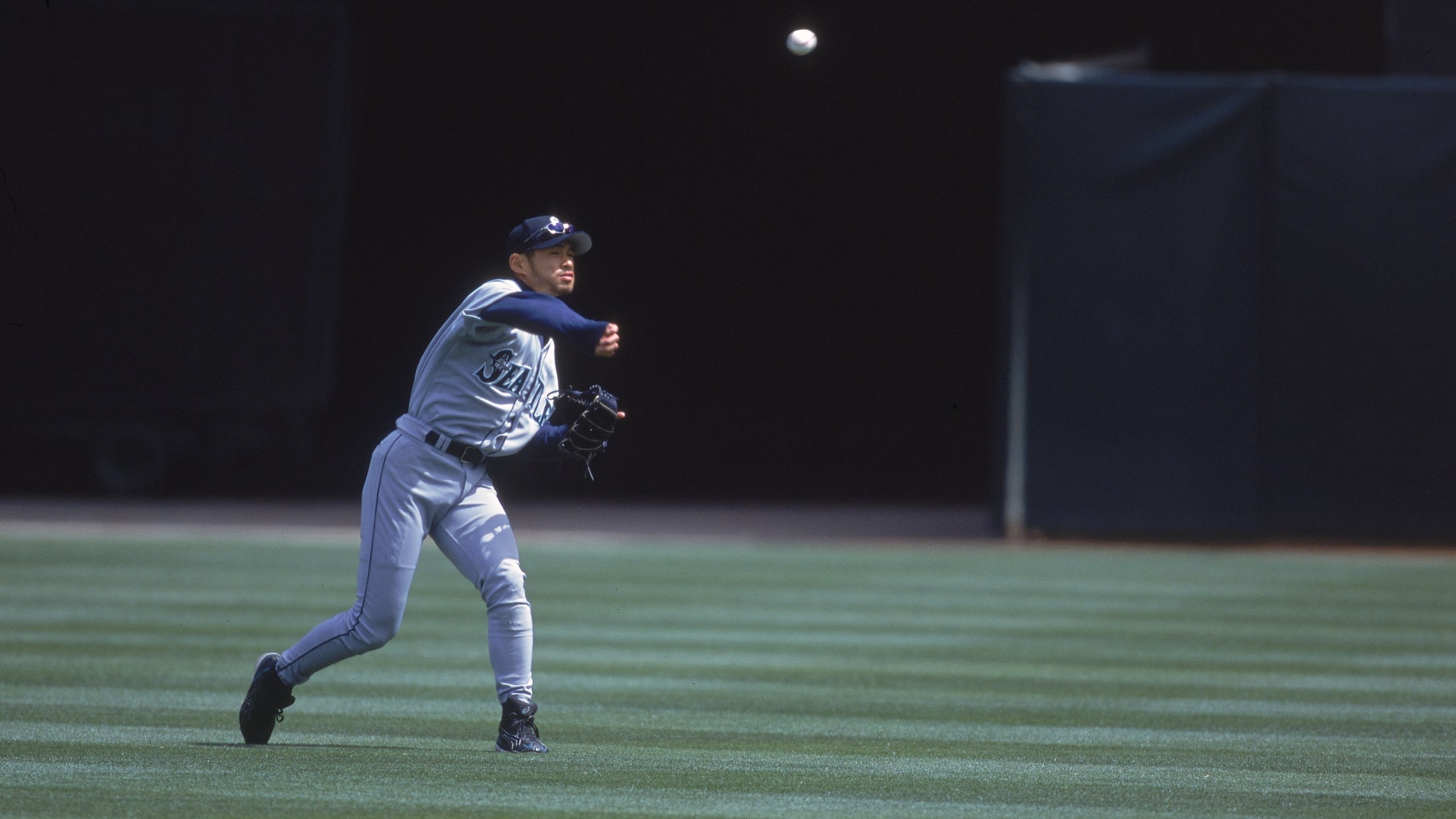

The Throw

Ichiro would come to be known for many great skills, but primarily his incredible ability to manipulate the bat and produce hits with a graceful -- and for opposing pitchers, maddening -- aplomb.

While he began to demonstrate that ability early on, it wasn’t his bat that truly announced his arrival in MLB and began to obliterate any preconceived notions of his talent.

It was his arm.

“We didn’t know much about him,” said Ramón Hernández, who had a 15-year Major League career as a catcher from 1999-2013. “We only knew him from Spring Training. We knew he was a guy who hit for a high average in Japan, and we knew he was really fast.

“But when I saw that throw …”

The throw Hernández was referring to was one that Ichiro made in Oakland during the eighth inning of his eighth MLB game. Hernández, then playing for the A’s, hit a ground ball into right field for a base hit. His teammate, Terrence Long, had been on first base. After the ball went through the infield, Long cut the bag at second and headed for third.

Given how the ball was hit and how it trickled into right field, going first to third was a no-brainer for Long, who possessed above-average speed. Most right fielders would be lucky to even get off a throw to third at all before the runner had almost reached the bag.

But as the A’s -- and the rest of the baseball world -- would imminently discover, Ichiro wasn’t most right fielders. As his first name suggested -- “Ichi” means “one” in Japanese -- Ichiro was 1 of 1.

He charged in hard, reached down to glove the ball, straightened up and fired a missile to third baseman David Bell on a line. Not only was Long out, Bell’s tag was waiting for him after Ichiro’s throw arrived virtually on the bag.

The frozen rope was so beautiful that the Seattle Post-Intelligencer’s John Hickey wrote that it needed to be “framed and hung on the wall at the Louvre next to the Mona Lisa.”

Hernández, Long, the A’s and the rest of baseball were now on notice: Ichiro was the real deal.

A Person, Not a Product

When Ichiro arrived in the Majors in 2001, a unique fusion developed involving how the world saw Japan.

“There hadn’t been many Japanese individuals who had starred on an international stage,” Lefton said. “Japanese product names were household names throughout the world, but not an individual. And Ichiro changed that.”

With the history of Japan being a leader in electronics and technology, it was only fitting that when an individual representing the country on the world stage emerged at the dawn of the 21st century, the development was paired with cutting edge technology that would enable millions back home to watch him shine on the other side of the globe.

The Mariners and Japan’s official carrier of MLB broadcasts, NHK, wanted to be sure that fans in Japan could follow Ichiro’s every move in the Major Leagues, so they wired Safeco Field (now T-Mobile Park) for high-definition telecasts that would be available in Japan.

While Ichiro hadn’t set any lofty goals of being a conduit for Japanese players to flow into the Majors, he does see how he opened access to MLB in Japan in terms of television consumption. While Japan was able to view MLB action every five days when pitcher Hideo Nomo came over in 1995, having a star position player was different.

“It wasn’t a motivation of mine to ‘open the door’ per se,” Ichiro said. “But when I did come and I started playing every day, that opened the door for people to watch baseball -- MLB baseball -- every day in Japan, whereas before, it was just every fifth day.”

A generation of Japanese children watched Ichiro make history and followed his career daily. Ichiro was a hero for kids like Ohtani, who watched Mariners games regularly as a young boy and went on to become a once-in-a-lifetime talent taking the Majors by storm.

Without Ichiro, would there have been an Ohtani? There’s no way to know that for sure, but it’s not unreasonable to assume the answer is no.

“Growing up, Ichiro was for me the way that I think some kids, some people, look at me today," Ohtani told GQ Magazine in 2023. "Like I’m a different species. Larger than life. He was a superstar in Japan. He had this charisma about him.”

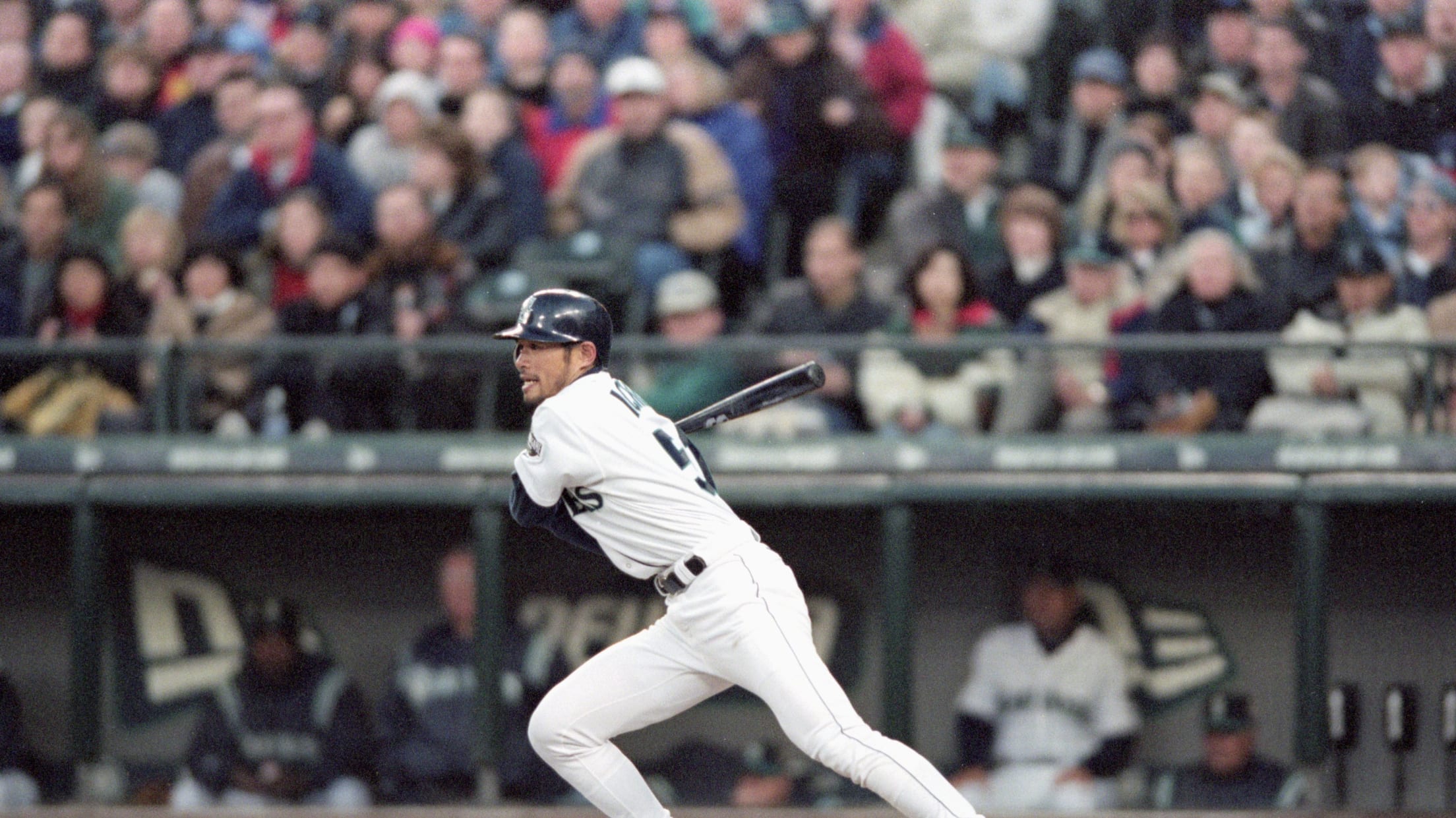

Ichiro’s charisma accompanied an incredible performance on the field, one that came with no discernable adjustment period. Among his many accomplishments, he became only the second player in Major League history to win his league’s Rookie of the Year Award and MVP Award in the same year, joining Boston's Fred Lynn (1975).

And the Japanese sensation did all of this against the backdrop of what was to that point the most prolific home run era in the history of the game -- in each of the previous three seasons and six of the previous eight, a new record was set for home runs across MLB.

Ichiro, with his masterful ability to “hit ’em where they ain’t,” was playing a beautiful game, and doing it his way, in the face of conventional baseball wisdom at the time. The stark contrast between his way of succeeding at the plate and that of others around the game likely contributed to the instant sensation he became in America.

But with his unique style, Ichiro paved the way for Japan’s sluggers. It has culminated in Ohtani. But before Ohtani, there was a contemporary of Ichiro’s who followed him to America and became a star on a big stage of his own.

A Seed Begins to Bloom

It was Game 2 of the 1999 AL Championship Series between the Yankees and the Red Sox, and among the 57,180 people in attendance in the Bronx that night was Hideki Matsui, then a star slugger for NPB’s Yomiuri Giants.

The thought of crossing the Pacific to play in the Major Leagues had certainly crossed Matsui’s mind before. But soaking in the electric atmosphere that night, he began to seriously consider the possibility.

“That was really what led to my desire to play in the Major Leagues,” Matsui said through interpreter Roger Kahlon. “It planted a seed.”

The seed had been planted, but somebody had to water it. Somebody had to be willing to be the first, to have the hopes of an entire nation riding on his shoulders. That someone was Ichiro.

As Matsui continued to ponder whether he would pursue the chance to play in the Major Leagues, he watched as Ichiro blazed the trail with astounding success.

A two-time All-Star and the 2009 World Series MVP for the Yankees, Matsui ultimately enjoyed tremendous success over 10 Major League seasons (2003-12). That can be attributed, at least to some degree, to Ichiro lighting the way before him.

“Since the games we got in Japan were primarily games in Seattle, on the West Coast,” Matsui said, “they were on during the day in Japan. It allowed me, prior to a night game, to turn on the TV and simply kind of kill time.

“And just by kind of watching while I was getting ready for my game, that’s how I sort of gained information about the Major Leagues. Rather than not having any information, having some information was certainly a plus.”

Now, with Ichiro on the verge of induction in Cooperstown, Matsui can’t help but look on with pride and happiness for his countryman and his country.

“I think it’s huge,” Matsui said. “When you think about it, baseball came from the United States. It wasn’t created in Japan. So in that sense, the impression was that Japanese baseball was always behind American baseball and trying to catch up.

“So for somebody who was born and raised in Japan, who played baseball in Japan and then actually competed in the U.S., to now make it to the Hall of Fame, it’s creating the impression that the gap between American baseball and Japanese baseball is much smaller.”

Matsui was just the first of many great Japanese players to follow Ichiro to MLB. But as Ichiro reflects on what’s transpired since he debuted in 2001, he sees both progress and much work remaining to be done.

And he remains at the forefront of that effort.

Still Running

At Mariners Spring Training camp in Peoria, Ariz., this past March, Mike Cameron was giving Ichiro a hard time. A former star center fielder for the Mariners and now a special assignment coach with the club, Cameron had a question for his former teammate, who himself is currently a special assistant to the club’s chairman.

“Man, you already got to the top,” Cameron said with a big smile, referring to Ichiro’s recent election to the Hall of Fame. “You’ve achieved everything. Why are you out here?”

Ichiro, noting that Cameron was asking the question tongue-in-cheek, recounted the conversation as he sat stretching in full uniform on the final Sunday before Opening Day.

The 51-year-old, who would four days later throw out the first pitch -- clocked at 84 mph -- prior to the Mariners’ Opening Day contest against the A’s at T-Mobile Park, began talking about where he is in his baseball journey, using Cameron’s light-hearted question as a jumping-off point.

“You know, I don’t look at [Hall of Fame induction] as the top,” Ichiro said. “This wasn’t the end goal. I still do have that desire of running out in front of people. That’s something that I strive to do and work hard at doing.

“By no means is this the top of the mountain.”

Following a legendary 19-year MLB career in which he had 3,089 hits and indelibly changed the game, that’s saying something.

At this point in the conversation, Ichiro paused and looked off into the distance, past batting practice on one of the back fields he had just come from. After pondering in silence for a full minute, he continued.

“I’m very honored to be in the Hall of Fame,” he said. “Definitely, it’s an honor. But I wanted to play the game to the best of my ability and accomplish things in the game of baseball -- it’s kind of a foundational belief of mine that I never wanted to say to myself, ‘Oh, I’ve made it because someone else told me I’ve made it.’

“This is just how I live my life. I don’t want others to determine my worth for me.”

Ichiro is still proving himself … to himself. But in doing so, he’s also continuing to move Japanese baseball forward. These days, if he’s not helping the Mariners, he’s back in Japan mentoring high school baseball players.

Many baseball fans have seen small bits of what he’s doing in training the next generation of Japanese players, interacting with youth players, high schoolers and pros. That includes some fun instances in which he has challenged those players in game action.

Despite all the progress over the past couple of decades, in Ichiro’s eyes, the work -- and the joy of it -- is far from done.

“When I do go over there, I want to really help them understand the good of baseball, and what baseball is all about,” he said.

It’s not a common sight to see a retired ballplayer in full uniform while throwing out a first pitch for his old club on Opening Day, as Ichiro did this past spring. But for Ichiro, it’s the only way that makes sense.

His baseball career is far from over, even in his early 50s. And that involves not just being around the game and teaching. It involves playing. It seems he will never stop playing the game.

“I think his focus,” Lefton said, “is maintaining a physical level where he can play the game to his satisfaction as long as he can. And he’s interested in being a teacher, so I think he feels like his message is lost if he can’t look like and move like a player.

“He’s much more of a ‘lead-by-example’ type of teacher.”

That’s not surprising given the example he set when he came to the Major Leagues nearly 25 years ago. It was a singular moment in baseball history that was pivotal in shaping the game for decades to come.

Indeed, Ichiro, whose name means "one" in Japanese but can also mean "first," is a pioneer of the highest order.

And as he takes his rightful place among the game’s most legendary players, his race is far from finished. As he did so often as a player when beating a play at first base for an infield single, he’s still sprinting toward the bag.

“I just keep running,” Ichiro said, “and see where it takes me. I’m just going to keep running.”