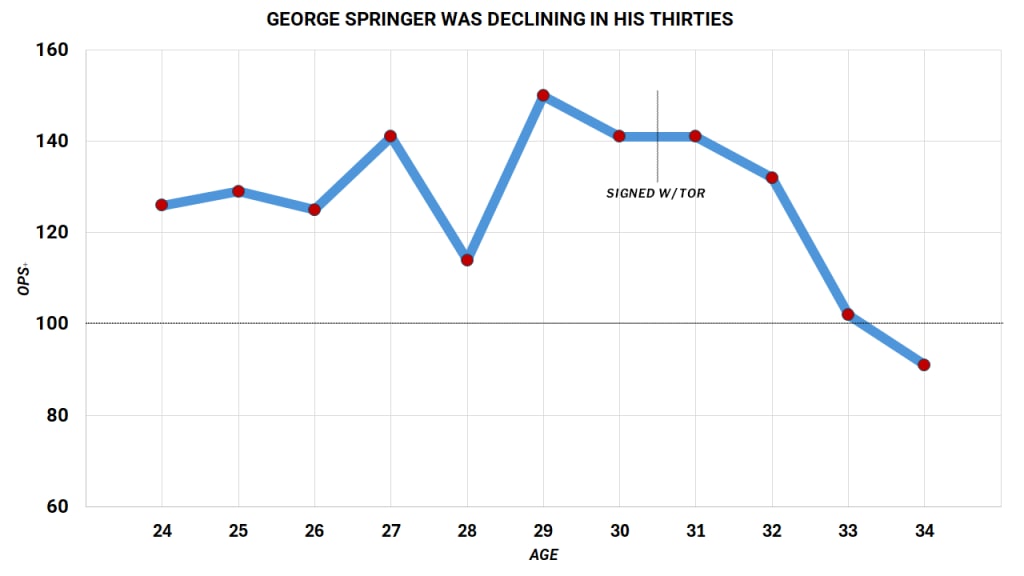

Below is what a perfectly normal aging curve looks like. This is George Springer’s career from 2014 through 2024, comprising his entire time with Houston and his first four seasons with the Jays after signing a six-year, $150 million contract prior to 2021. (We’re showing OPS+, which puts 100 at league-average for that year.)

For years, Springer was was consistently solid-to-excellent, and then, for the 2023 season, he turned 33. Worse: the next year, he turned 34.

This is what happens, more often than not, for high-level hitters. When the Jays handed out that contract, covering Springer’s age 31-36 seasons, they knew what they were signing up for. They were expecting continued excellence for the first few years – which they received for the first two years, though he did miss time with various leg injuries – and then you hope for a soft enough decline that by the end of the deal, the player can still be a supporting piece, if no longer a central star.

If that was all happening maybe a year sooner than they’d have liked, that’s how it was trending. In his first two seasons in Toronto, Springer remained a high-level bat. In 2023, at 33, he was a league-average bat; in 2024, at 34, he was mildly worse than that. For 2025, projections hoped for a mild rebound, to the roughly-average range. It’s what happens at 35. The historical trends don’t lie.

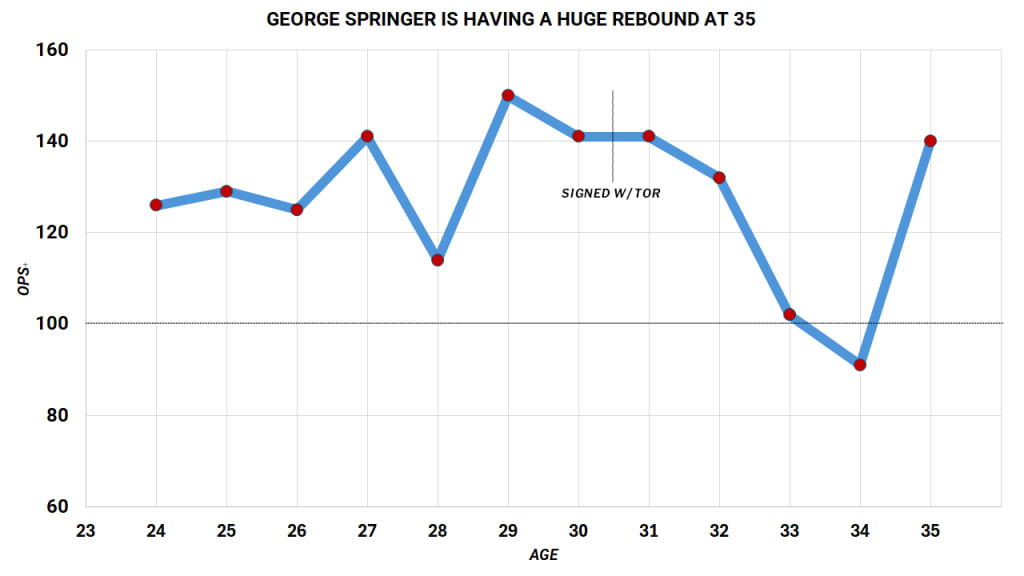

Except, apparently, when they do.

Springer, entering Tuesday night's game against the White Sox, was hitting .276/.368/.503, good for a 140 OPS+, his best since 2019. He’s been the best hitter on a stunningly good Blue Jays team that is riding a nine-game winning streak. He’s the best 35-or-older hitter in the game this year, which undersells it a little, because over the last decade, only two hitters have hit this well at this age or older: Nelson Cruz and David Ortiz.

Name an important metric, and he’s among the most improved in it from 2024. Springer has the third-largest jump in OPS, fueled in large part by the fourth-biggest drop in ground ball rate and the seventh-largest jump in barrel rate. (Another way of saying that: hit it harder and in the air more.) Only Cal Raleigh and Pete Crow-Armstrong have added more slugging; put it all together, and Springer has the second-largest jump in Statcast’s expected quality of contact, just ahead of breakout star Crow-Armstrong.

All of which might say as much about how well he’s hit this year as it does about how concerning the trends were last year – there’s a reason you don’t see Aaron Judge or Shohei Ohtani on ‘most improved’ lists, after all. That this also comes after one of the weakest Spring Training lines of his career (.108/.298/.216) is also a nice reminder how little those numbers end up meaning.

So: What’s really different here? For a moment, in April, when he had his highest BABIP mark in nearly a decade, it felt like “good luck,” but here we are three months later, and it’s not good luck. Fortunately for us, Springer and the Jays coaching staff were pretty up front about the plan entering the season. It was about the intent to do more damage.

“For George, it’s pretty simple. I want him to take one ‘A’ swing every single at-bat and swing at good pitches,” said manager John Schneider to MLB.com’s Keegan Matheson in Dunedin this spring, in the midst of Springer’s concerning March lack of performance.

“It just seemed like he kind of lost that aggression that he's had his whole career, that I've always admired from him,” first-year hitting coach David Popkins told Sportsnet’s Ben Nicholson-Smith shortly after the season began. “You’d see him kind of sacrifice bat speed just to put balls in play and really reaching for balls and weak contact early. Almost like he’s scared to get to two strikes. Versus the best version of him I feel like is not afraid to take a couple borderline pitches and then if you make one mistake he’s going to hit it really hard.”

It might be a perfect distillation of the modern hitting approach to offer “[don’t] sacrifice bat speed just to put balls in play,” surprising though it may be coming from the hitting coach of a Toronto team that has the lowest year-adjusted strikeout rate in the 49-season history of the franchise.

That’s all a pretty clear attack plan, so let’s prove it out. If “the best version of him is .. not afraid to take a couple borderline pitches,” let’s call that pitches on the edges of the zone, thrown before the count gets to two strikes. Those edges are a place where Springer was indeed finding that weak, early-count contact – hitting just .160/.259/.181 last year, with a mere 81 mph average exit velocity and a poor 26% hard-hit rate. No batter in baseball did more damage to his own value in that particular situation last year than Springer, who cost a whopping 24 runs just on those early-count edge pitches.

Springer, as advertised, is swinging at those pitches less this year than in any previous year of his Blue Jays tenure, and about as often as he did in his best years in Houston.

Swings on the edges before two strikes

- 2021 // 41%

- 2022 // 50%

- 2023 // 45%

- 2024 // 44%

- 2024 // 39% ←

It’s true that Springer went after those pitches a lot in 2022, when he was an All-Star. It’s true that Springer wasn’t 35 years old back then, either.

It might cause you to eat a strike, sometimes, even one you could have connected with. But as Schneider told Matheson in April: “We spent so much time with George talking about that. We’d rather you be 0-and-1 than 0-for-1,” which is a quote we may get framed.

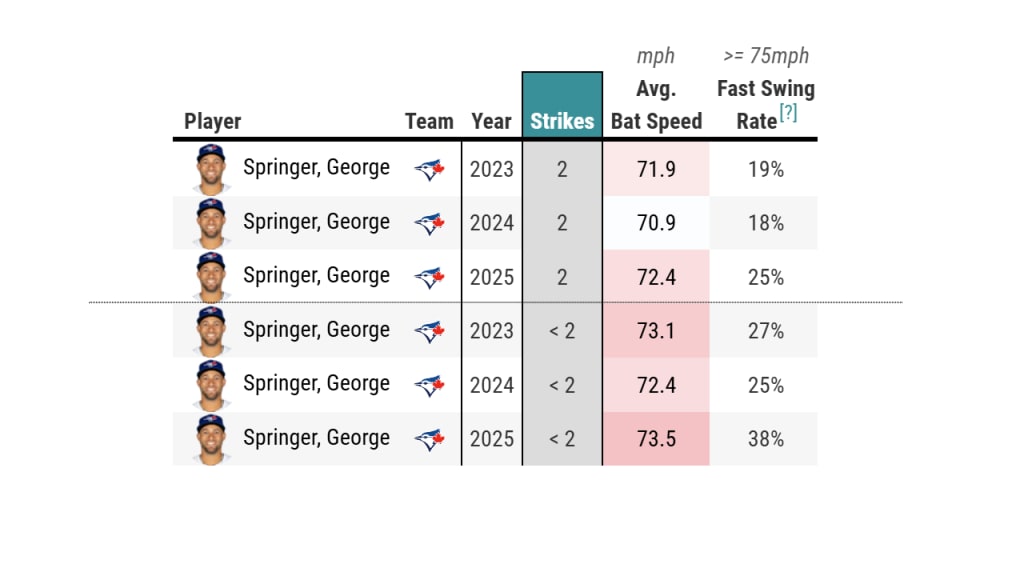

OK, so you’re not swinging as often at pitches you can’t damage, just to say you made contact. What’s next? Let’s talk about that "A-swing" and not sacrificing bat speed – an important issue for Springer, as it is for any hitter this side of Luis Arraez. Since 2023, when Springer swings harder than his three-season average of 72 mph, he’s outstanding: .308 average, .563 slugging. When he’s swinging under that? .187 and .252. It’s stark.

For some hitters, improving bat speed is about physical training, about getting stronger. For others, it’s about choosing better pitches to go after. For still more, it’s simply about intent.

It seems clear Springer is going after better pitches. As team broadcaster Dan Schulman recently relayed, Springer went into 2024, trying to be on base ahead of Vladimir Guerrero Jr., but ahead of this year, “his goal is to hit the ball out of the ballpark.”

It seems pretty clear there’s intent at play here, too.

Well, OK. There’s really two things you need to do to hit for power, and that’s “swing hard to hit it hard,” and “hit it in the air.” As we shared above, Springer’s decline in ground ball rate from 50% to 39% is one of the largest in the Majors. It’s not terribly hard to see why, aside from swinging at better pitches: Springer’s attack angle, or the vertical angle at which the bat is traveling at the contact point – think of it as being to the bat what launch angle is to the ball – had dipped to a mere 6° in the early part of 2024. But it has jumped to 13° this year. Springer's swing path, or the shape of his swing on the way to the ball, is up, too. None of this is accidental.

Given all of that – swinging at better pitches, going up there with an intent to do damage – you’d expect to see an increase in bat speed. Sometimes the puzzle pieces fall together easily. Springer is clearly swinging harder before two strikes this year, with a fast-swing rate (a swing 75 mph or harder) jumping from 25% to 38%, and there’s that intent.

He’s swinging harder on two strikes, too, and though that’s still a bad position for a hitter to be in – Springer, like everyone else, is considerably worse on two strikes – his first of two homers on Canada Day came off a two-strike breaker from none other than Yankees All-Star Max Fried.

All of which is important because almost nobody in the game lets the ball get deeper before making contact. That’s fine if you’re Juan Soto, who has elite bat speed and can let the ball get that deep before unleashing the swing. It’s a lot harder when you have average or below-average bat speed, as Springer was trending.

Take it all together, and Springer has turned around what seemed to be an irreversible trend, which is that he was getting eaten alive with fastballs. He slid to a .241 average and .387 slugging percentage last year before rebounding to a .325 BA and .564 SLG in 2025.

Springer, for all his achievements, is still 35. The only thing for certain is that come September, he’ll turn 36. He’s already made some concessions to age, first moving from center to right field in 2023, and now spending half of his time at designated hitter, which potentially takes some stress off the legs. He’s not a leadoff hitter any longer, either, spending most of his time hitting fourth or fifth.

But for the moment, it’s not hard to see what he’s done to arrest the aging curve. All it took was making some pretty massive changes to way he approaches the pitches that he sees. Nothing hard about that, right?