The war, such as it was, is over. The new style has won.

Every catcher in the Major Leagues receives with a knee down. Most of them do it 95% of the time or more. It makes it easier to frame pitches, which is quite valuable. It doesn’t come with the cost of making it more difficult to block, contrary to popular opinion. It might have secondary effects about wear-and-tear. What was a curiosity a mere handful of years ago has now completely taken over the sport. It’s hard to see it ever going back.

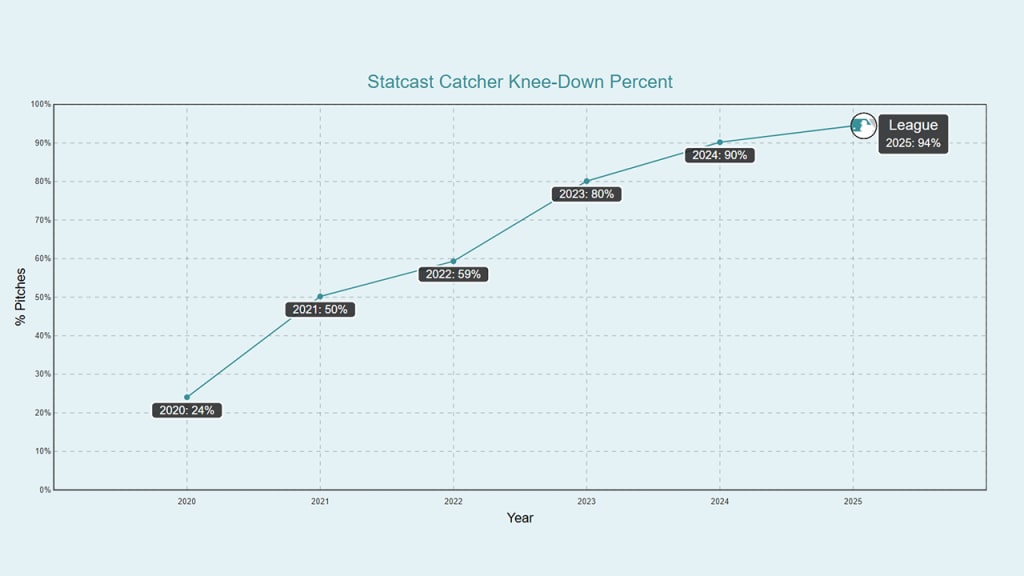

It’s been easy to tell because it’s easy to see; it didn’t take social media very long to realize that every starting catcher on Opening Day this year was down on a knee. It’s also been studied extensively, primarily here at MLB.com and by JJ Cooper at Baseball America. But really, it’s time to make it as clear as possible. With the addition of Statcast’s catcher stance data to Baseball Savant, the numbers are there. It’s hard to look at this trendline and not see what’s happening.

It’s actually more than that, really, since the one remaining traditional holdout, Austin Barnes (23% knee-down rate) was released by the Dodgers on May 14. (He has since signed a Minor League deal with the Giants.) With him no longer in the bigs, the Majors were up to 96% of pitches being received on one knee in June, which is to say, “almost everyone all the time.”

We’d give you a leaderboard, except it would just be something like a 60-way tie at “98 to 100% of the time,” with 35-year-old veteran Kyle Higashioka the only current catcher not using the stance at least 50% of the time – and even he’s using it more than four times as often (41%) as he did just a season ago (9%). While Higashioka has admittedly not been a strong blocker this year, he was also one of the weakest over the last two seasons, primarily using the traditional stance.

It’s so pervasive that the one catcher this year who decided to go against the style of the time, to abandon the knee-down stance for a more traditional setup – Logan O’Hoppe of the Angels, who did so in mid-May – lasted barely a month before returning to the knee down in early June.

Full stop, then, for a moment: If it didn’t make sense to do it, then every catcher in the sport wouldn’t agree to be doing something that made their performances worse. It would be shared lunacy across the game.

The numbers make it clear enough why it’s happening. Passed balls and wild pitches per game in 2025 are exactly what they were in 1960, and are at their lowest rate since 1981. There’s no appreciable difference in the share coming with a runner on third – i.e., the most important blocking situations – either. There’s no reason to think that pitchers, fearful of one-kneed catchers being less likely to block breaking balls in the dirt, are choosing to throw less of them. If anything, they’re throwing more.

This spring, two-time AL Manager of the Year Kevin Cash of the Rays, who caught in the Majors for eight seasons, told the Tampa Bay Times this: “When you take a 1-1 pitch and help turn that pitch into a strike as opposed to a ball, that is way more valuable doing that three times than a ball getting by you to advance a guy from first to second.”

Since 2020, and through Wednesday, catchers in a knee-down stance have been worth +169 fielding runs, while those with both up cost their teams -152 runs. It’s worse than it sounds, because traditional catchers received only one-third as many pitches in the first place.

It’s easy to see if you break down the skills, too. Blocking pitches? Since 2020 …

PB+WP/100 pitches

- Both knees up: 0.6

- Knee down stance: 0.6

… it’s identical. Since the focus is so often on pitches in the dirt, it’s worth noting that the new method is ever so slightly better on breaking balls (1 missed pitch per 100 in the traditional stance vs 0.9 in a knee-down stance), which makes some sense, given the lower setup. While this might seem a little about the 2023 introduction of Pitchcom, which reduces the chances of cross-ups, the story is the same from 2020-'22, too.

That might not be a large margin, but it’s certainly not worse. If a knee-down catcher is still capable of making a bad miss on a ball that should be blocked, it’s mostly a good reminder that, as of yet, nobody has invented a method capable of blocking 100% of pitches perfectly.

Baseball's two best blockers this season, Toronto's Alejandro Kirk and Boston's Carlos Narvaez, receive with a knee down 95% and 91% of the time, respectively.

Framing? Again since 2020 …

Called Strike rate on edges

- Both knees up: 45%

- Knee down stance: 47%

That’s an easy win there, with the interesting note that it does matter which knee is down here. With a righty batter at the plate, having the left knee down (49% called strike rate) is considerably better than the right knee down (45%). Having both knees down (48%) splits the difference.

What about throwing? Given the rule changes in 2023 that made stolen bases considerably easier, let’s look at just the last three seasons for this one.

Caught Stealing Runs Above Avg. per 100 attempts

- Both knees up: 0.3

- Knee down stance: 0.2

Potentially a mild edge for the traditional way, though worth it for the other gains, and regardless: it’s extremely noisy per-season. That is, in 2023, the knee-down method (+0.2) was better than the traditional (-0.2); in 2024, old (+1) beat new (-0.6), and so far this year, knee-down is far more effective, providing +1.4 run/100 of value compared to the 0.4 run/100 of value for the old way.

Of course, "the old way" implies that this was a style invented just recently. While Yankee catching coach Tanner Swanson is largely credited with the modern takeover of the method, it's hard to watch this highlight of Ron Guidry pitching in 1979 without noticing exactly how his catcher, Brad Gulden, is set up. (Don't miss the praise he's receiving from the broadcasters, too.)

And surely, when you look at this classic photo of all-time legend Bob Feller preparing to pitch to all-time legend Hank Greenberg from way back in 1939, you're only focusing on two Hall of Famers in their pre-war primes -- not the way that the Cleveland catcher (either Frankie Pytlak or Rollie Hemsley, though it's impossible to tell which) is set up. Right?

But there’s something else happening here, beyond just the obvious “it helps framing and doesn’t hurt blocking” of it all. What about how it affects the players playing the most difficult position on the field? It’s worth hearing exactly what they have to say – and they’re saying something compelling about what the different stance means physically.

“I think it saves him physically a lot of wear and tear," said then-Phillies manager Joe Girardi, himself a 15-year catcher, regarding J.T. Realmuto moving to a knee down in 2021. “There are some elements that make it less taxing,” noted Red Sox coach Jason Varitek (a three-time catching All-Star) around the same time. Even late converters, like Rays catcher Danny Jansen, who had a knee down just 33% of the time from 2020-’24 before going to 95% this year, said this spring that the stance is “less taxing.”

Or realize how Cleveland skipper Stephen Vogt, a two-time All-Star catcher and 2024 Manager of the Year winner, put it last year.

“They’re going to be able to play more. They’re going to be able to play a lot longer. They’re not going to take the pounding and the wear and tear in their knees and hips and back like a lot of the traditional catchers did.”

We can’t really prove ‘freshness,’ or saved wear-and-tear. But anecdotally, we can at least note this: Catchers do seem to be playing more now, reversing a recent trend.

Consider this: In 2022, only nine catchers even made it to 400 plate appearances, less than half of the 22 such catchers we’d seen less than a decade before, in 2014. It was also a full-season low dating all the way back to 1967’s eight – when, of course, there were only 20 teams. Understanding that injuries can and will pop up as the summer progresses, we’re currently on pace for 22 catchers to hit 400 plate appearances in 2025.

So, given all that, why did O’Hoppe change his mind – and then un-change it? At the time, he told the Orange County Register that he was frustrated with his poor blocking and receiving numbers, and that he found the stance uncomfortable. Fair enough; few things are one-size fits all. But when he went back, it was because the performance hadn’t improved, and worse, may have contributed to an incident between the Angels and Red Sox coaching staffs precipitated by O’Hoppe’s setup giving pitches away.

“The numbers still sucked,” he told Jeff Fletcher. “I haven't felt good behind the plate all year."

While he was twice as likely to miss a passed ball or wild pitch with the knee up, he’s right that the numbers haven’t been positive either way. Sometimes, it’s not about the strategy, and it’s more about the player implementing that strategy.

Catching, like the rest of the game, keeps on evolving. There was a point in time where all catchers received standing up, you might remember, and didn’t even wear face masks. (That was the 19th century, but still.) For decades after, the style was to catch with two hands, until Randy Hundley, Johnny Bench and friends discovered one-handed catching worked just fine while better protecting the throwing hand. Bench was also among the first to wear a hard-sided helmet to protect the back of his head from backswings, which decades later led to the hockey-style mask that almost every backstop sports today.

This may or may not be the final form of the art. It’s not hard to see some enterprising backstop finding something new a decade from now, and then realize that everyone else follows that lead. The catching world evolution didn’t end when the two-handed receiving style morphed into the one-handed style. It’s not going to end because of a knee down, either.