Mother’s Day is an occasion on which we celebrate the love, nurture, selfless sacrifice and powerful impact of mothers everywhere.

But amid that celebration of motherhood there are some who experience profound sadness. For those who lost their mothers too soon, Mother’s Day can be a painful time.

So it was for longtime A’s radio broadcaster Ken Korach on the morning of May 9, 2010.

As he drove to the Oakland Coliseum to call the series finale between the A’s and the Rays, he looked up at the sky.

“It was kind of a gray morning in the Bay Area,” Korach said. “And that’s the way I felt.”

Korach’s mother died when he was 21. And every year since, Mother’s Day had been a day he did not look forward to.

“It wasn’t a day of celebration for me,” said the 73-year-old. “Now, my wife and I have been married since 1988, and we have a wonderful daughter -- I don’t want to discount the fact that I love my wife, and from that standpoint Mother’s Day is still important.

“But in terms of thinking about my mom that day, I think about her all the time. And I think my mood matched the sky that day.”

What Korach didn’t know as he arrived at the ballpark was that by the end of that day, Mother’s Day would never be the same.

From that day forward, he would see it in a different light because of what transpired in Oakland that afternoon -- something so unexpected, so improbable and so inspirational that the broadcaster of over 40 years says he has never been more emotional while behind the microphone.

“The memories of that day will last forever,” Korach said. “And they do bring a positive shading to what was otherwise a dark, gloomy day.”

Those memories center around another man for whom Mother’s Day was a difficult time. In fact, it was a day he dreaded.

But all of that changed on that day 15 years ago.

Miserable

As Korach was heading to the Oakland Coliseum, Peggy Lindsey was driving to her grandson’s house in Stockton, about an hour east of Oakland.

She did that every morning on days her grandson worked. She would check on the dogs, feed the fish and just make sure all was as it should be after he had left.

But on this day, all was not as it should have been.

As she approached the house, she realized that her grandson hadn’t left yet. His car was in the driveway, and when she opened the front door, she saw beer cans strewn across the living room.

“I was thinking, ‘What are you doing?’” Peggy remembers. “‘Why haven’t you gone to work?’”

The reason Dallas Braden hadn’t gone to work was because this was a day he wished he didn’t have to live through each year.

Mother’s Day, for Braden, meant unbearable pain ever since his mother died of melanoma when he was 17 years old.

“I had made peace with the fact that I didn’t want to deal with Mother’s Day,” Braden said. “I would just go numb. So I had some friends over to the house the night before and they were going through it with me, if you will.”

When his grandmother walked in and called his name, he slowly emerged from his room.

“When Dallas is in that frame of mind, he doesn’t want to talk to anyone,” Peggy said. “It was just, ‘Leave me alone, I’ll do it.’”

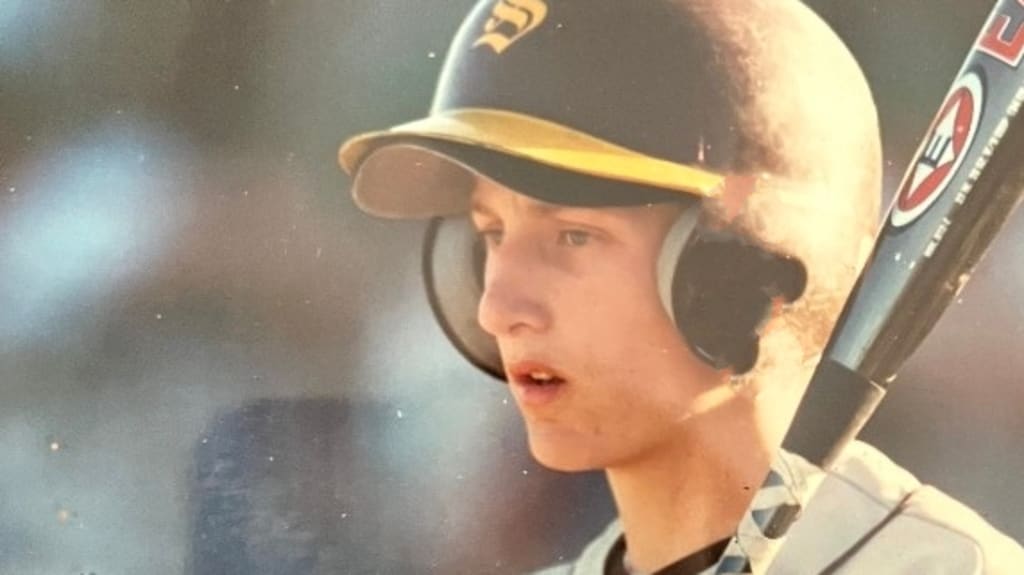

In this case, what he needed to do was get ready for work. Braden was a starting pitcher for the A’s, and he was scheduled to take the mound in three hours against the Rays, the team with the best record in baseball.

Peggy, as she did every time Dallas pitched at home, drove to Oakland, hoping that he would follow.

“I had some friends and we rode together and did the tailgate thing,” she said of game days. “I never missed a game when he pitched in Oakland.”

Braden did follow, though he was certain that everything about this day would be, as he put it, “miserable.”

“I just didn’t look forward to having to be around anybody,” he said. “I didn’t look forward to having to get in the car and drive through traffic to get to the ballpark. And I felt like absolute trash.”

With an hour to himself as he drove to the ballpark, Braden couldn’t help but think of the fact that his mother never saw him make it to the Major Leagues. It only intensified the anguish of missing her as he remembered everything she did for him -- and how his dream was her dream.

From his earliest years, she taught him about integrity, work ethic and perseverance, all lessons that were central to what he had achieved to this point. But more than that, she demonstrated her love for him through the many sacrifices she made.

She was making it happen

When Braden was in grade school, he would get his homework done within the 10 minutes he had between the time he received the assignment and when the final bell rang to signal the end of the school day. And he did very well on those assignments.

There was just one problem.

“I wouldn’t put my name on it, and I’d just shove it in my desk,” Braden said. “At a parent-teacher conference, I can remember the teacher had like 15 or 20 homework assignments saved, but none of them had my name on it.

“And they were all perfect.”

When the teacher explained the anonymous perfection issue to Dallas’ mother, Jodie Atwood, it presented an opportunity for Jodie to instill a principle in her son that took him far beyond what he could ever have imagined.

"This is the only way that people are going to know what you’re capable of,” she told him. “You have to put your name on your work.

“Remember, this is what people will see. This is what people will take away. If they’ve never met you and don’t know you, and all they have is the opportunity to evaluate something like this, your name is attached to it.”

Braden would sometimes miss school in order to help with Jodie’s house cleaning business. That’s because the business only had one employee -- a single mother who was devoted to affording her son the chance to achieve his dreams.

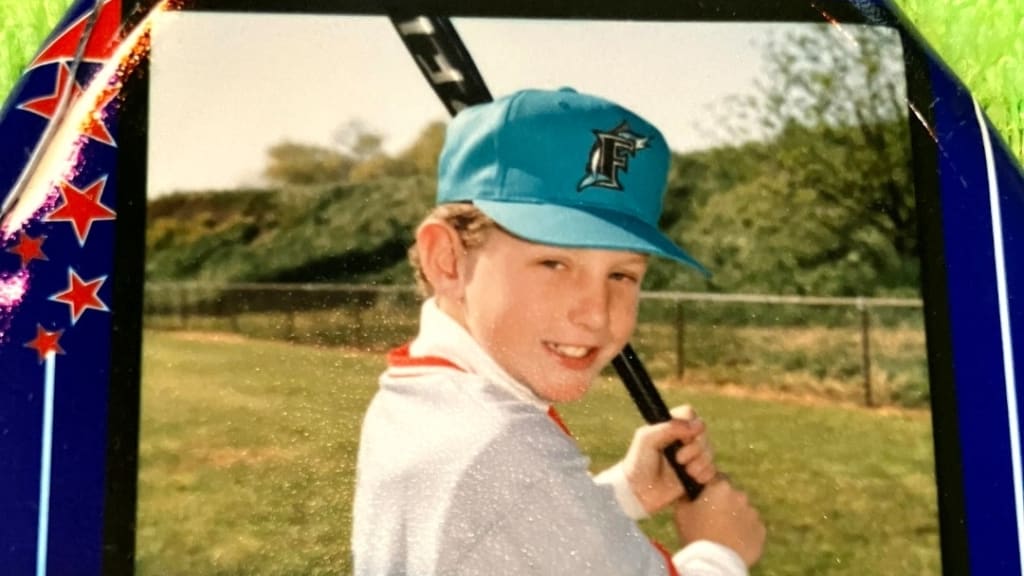

When Braden began playing baseball at four years old, he instantly fell in love with it. And he wanted what he calls “the best game on Earth” to be his future.

For his mom, that meant tirelessly cleaning houses and even moving to another neighborhood in Stockton so that Braden could play Little League.

“Everything that woman did was geared towards me being able to play baseball,” Braden said. “Everything in our life was geared toward watching baseball, playing baseball. However it could happen, she was making it happen.”

For Dallas, it meant occasionally accompanying his mom so they could clean an extra house or two that day.

Through that experience, Braden learned much more than how to mop his way out of a room or “leave those little triangles” with a vacuum.

“For me,” he said, “the takeaway was the work ethic, the attention to detail and the diligence -- when you start something, you finish it.”

Starting something

Normally, on a day when he was scheduled to start on the mound, Braden arrived at the ballpark about four hours prior to the game. But on this day, he arrived at the Oakland Coliseum at about noon, with first pitch scheduled for 1:08.

He didn’t have time to go through his normal routine.

“Everything was completely thrown off,” Braden said. “With my OCD, I’d clean my cleats, I’d oil my glove, I had a stretching routine. I would go get a massage. I would go over the lineup again after studying it throughout the week.

“But now I couldn’t do any of that.”

All Braden could do is warm up in the bullpen and then take the mound. As he led his teammates out to the field under overcast skies, he was thinking about the potential ramifications of the choices he had made over the prior 24 hours, including his decision to stay up drinking into the wee hours of the morning instead of getting a good night's sleep in anticipation of his start the next day.

“The way I felt physically was self-inflicted, so there’s no excuse here,” Braden said. “I’m trying to be as mentally accountable as I can because my biggest responsibility that day is to my teammates. So I was already battling with how I’ve let my teammates down because of the selfish decision I made to process my emotions the way I did.”

As those thoughts went through Braden’s mind, Rays shortstop Jason Bartlett stepped into the batter’s box to lead off the game for Tampa Bay.

Braden opened the contest with a first-pitch strike on the outside corner at 85 mph. On the next pitch, using a pink Mother’s Day bat, Bartlett smashed a line drive over third base that looked destined for the left-field line.

But third baseman Kevin Kouzmanoff leaped and speared it on the backhand for the first out of the game.

“Jason Bartlett with a potential double down the left-field line to start the game,” Braden said. “That’s how that game should’ve gone, right? I mean, the guy who got wasted the night before and comes out late to the game -- that guy should be giving up a leadoff double, not having it snared out of thin air.”

Carl Crawford was next, and he grounded out to first base. He was followed by Ben Zobrist, who flew out to center fielder Rajai Davis.

In the Rays’ second, Evan Longoria led off with a flyout to center field. Carlos Peña then smashed a hot shot to first base, where Daric Barton stuck with a bad hop and went to the bag for the second out. Braden completed the second inning with a strikeout of B.J. Upton.

It was an auspicious start to his outing, particularly given how Braden was feeling. But it was nothing extraordinary.

That would come later.

Something you don’t fix

“It was just my mom and my grandma.”

Braden’s childhood was one of difficult straits.

“They had to figure out where our food was going to come from, they had to figure out where money for housing was going to come from,” he said. “Those were all very real issues that we were dealing with.

“For me, it was like that song -- you’re so poor, you don’t even know you’re poor.”

Braden’s father wasn’t a consistent presence. The way he described his father's involvement in his young life was “in and out.”

So it was the trio of Jodie, Peggy and Dallas. It was them against the world.

Peggy ran a Super 8 motel in Stockton. She worked 16-hour days and lived in an apartment on the premises, and Dallas -- whom his mother and grandmother called “Dal” -- lived in one of the motel rooms.

The high school years were turbulent.

“I was not with a good group of people and I was making very bad decisions,” Braden said. “And we all know where those roads lead.”

Braden, by this point, was a star pitcher at Stockton’s Amos Alonzo Stagg High School. The mound was his refuge from the difficulties of life, but harsh reality awaited off the field.

It all came to a head in May of 2001, as Braden was preparing to become the first member of his family to graduate from high school.

He found himself in a doctor’s office trying to process the unfathomable. As he stared in disbelief, he was told that his mother had melanoma that had metastasized.

“We must have missed something in the bloodwork,” the doctor said. “It’s gone to her brain. It’s inoperable.”

“I went absolutely berserk,” Braden said. “I lost it. It was a bad scene.”

A few months later, while out eating with a friend, Braden got a call from his grandmother. Before even answering, he knew.

“Dal,” Peggy said. “You need to come home.”

When he entered his grandmother’s apartment, he saw something he refused to accept. A week after Mother’s Day in 2001, Jodie Atwood passed away at the age of 39.

As Peggy tried to tell her grandson that his mother was gone, he was inconsolable.

“No!,” he yelled. “No, Gran, no!”

“When he was a little kid, he’d come to Gran and he thought I could make everything better,” Peggy said. “He would always say, ‘Gran’ll fix it. Gran’ll fix it.’

“But this was something you don’t fix.”

Tunnel vision

When Braden walked out to the mound to begin the third inning, his lineup had given him a lead by scoring a run against his counterpart, James Shields.

Braden caught Willy Aybar looking at strike three for the first out, then got flyouts from Dioner Navarro and Gabe Kapler.

The A’s picked up another run in the bottom of the third before Braden went out for the fourth. It was back to the top of Tampa Bay's lineup as Bartlett dug in.

After working the count full, Bartlett tapped a slow roller to third. With his above-average speed, it seemed the Rays might have their first hit of the game.

But Kouzmanoff charged in, gloved it and fired a seed to first, where Barton stretched to the limit to receive the throw. Bartlett was out by half a step.

Braden struck out the next batter, Crawford, and then induced a ground ball to short off the bat of Zobrist.

As he walked off the mound, Braden knew things were going well, but he didn’t think it was anything special.

“Honestly, I wasn’t surprised at how it was going,” he said. “It’s not like I was punching people out and it was crazy. There was weak contact. And when I’m gonna have a good game, that’s what’s happening.”

Braden’s catcher, though, knew he was on point. That’s partly because he knew him so well, having been drafted in the same year and coming up through the Minors with him.

“The number one factor was his screwball,” said Landon Powell, who was behind the plate that day. “It was kind of like a changeup, but it really was a screwball. That was really his bread and butter.

“And he would throw the fastball inside to right-handed hitters, which added a little bit of effective velocity -- if he’s throwing an 88 mph fastball on the inside corner, it feels like 92 mph because of the differential between that and his screwball. He just kind of sped hitters up and kept them guessing.”

In the fifth, with the A’s now leading, 4-0, Braden struck out Longoria swinging, got Peña to fly out to left and got Upton to ground out to third.

15 up, 15 down.

Braden was still numb. It was, after all, the worst day on his calendar -- a day on which he was reminded at every turn of his incalculable loss.

Whether it was the pink bats, the pink armbands, the "Happy Mother’s Day" signs in the crowd or something else, the triggers were everywhere.

But he said the numbness, in a strange way, helped him on the mound.

“It was just tunnel vision,” he said.

The Lighthouse

Braden affectionately refers to his grandmother as “Gran.” But he also has another name for her.

“I call her ‘the Lighthouse,’” he said. “She’s incredible. To know her is to have a vibe for how my mom was. She’s much sweeter these days, but she’s still a ball of fire.”

A lighthouse is what Braden needed after his mother died. At 17, having experienced that type of trauma and emotional upheaval, it would take a steady and patient hand to help steer his ship through the night amid tumultuous waters as he reached adulthood.

Peggy Lindsey was there to provide it.

“Peggy was so incredibly instrumental because she kept Dallas on the right path,” said Korach, who got to know the two well. “It could’ve gone the other way. He was kind of teetering on the edge back then, in terms of his own stability as a person.”

After Braden graduated from high school, he told his grandmother that he didn’t want to go to college in Stockton. There were just too many painful memories in his hometown.

So Peggy took him to American River College in Sacramento.

“I talked to the baseball coach there,” she said. “And I said I have a grandson who needs to go to school and needs to play ball.”

The coach said that the roster was already full.

“He’s a left-handed pitcher,” Peggy replied. “And he was drafted by the Atlanta Braves.”

That did the trick.

Braden had been drafted out of high school as a 46th-round pick by the Braves, but he didn’t sign. He instead considered joining the Marine Corps.

But thanks to the encouragement of a recruiter for the Marines and the help of his grandmother, he went on to star at American River and then transferred to Texas Tech, from which the A’s drafted him in the 24th round in 2004.

It was a bittersweet moment.

“My mom never saw me get drafted,” Braden said. “That was our goal. That was our dream.”

In April 2007, Peggy got a phone call from Dallas, who was by then pitching for the Athletics’ Triple-A affiliate in Sacramento.

“He said, ‘Gran, they’re sending me back,’” she remembers.

Peggy thought he was saying he was being sent back down to Double-A in Midland, Texas.

“No, Gran,” Braden said. “They’re sending me back east, to Baltimore. So get your suitcase packed.”

Braden flew her out to see him make his Major League debut against the Orioles at Camden Yards on April 24, 2007.

“He was nervous all day,” Korach remembers. “He was worried that his grandmother wouldn’t get there on time to see the game.”

Peggy made it in time, and with her in the stands and the seat next to her -- where Jodie would have been sitting had she been alive -- empty, Braden went to work.

The 23-year-old pitched six innings, yielding only one run on three hits while walking one and striking out six in a 4-2 A’s victory.

Later, the fan who had the ticket for that afternoon’s game in the seat next to Peggy's, but didn’t attend, gave the ticket to Braden as a keepsake.

Don’t baby it

Braden opened the sixth inning with his second strikeout of Aybar. Navarro was next, and he popped out to Kouzmanoff in foul territory.

Up stepped Kapler, who quickly fell behind, 0-2. But he battled in what would become a 12-pitch at-bat before Braden won, getting him to pop out to Kouzmanoff again in foul ground.

When Braden got back to the dugout, no one would talk to him out of fear they might somehow disrupt what was happening or "jinx" it. But silence from his teammates wasn't unusual when he pitched.

“On my start days, I spoke to no one,” he said. “The other four days in between starts, I’ll talk to a fence post. I’m best friends with the fly on the wall.”

“On days he starts, he’s locked in,” Powell said. “It’s like he’s going to war. He’s not smiling, he’s not joking. His game days, he’s like a UFC fighter. And everyone knew that about Dallas -- if it was his game day, just let him do his thing.”

As Braden sat in silence, he realized something.

“I started to take note of what was going on,” he said. “I realized that no one had reached base.

“So we had a conversation, me and myself. I stood up and said out loud to myself, ‘Alright. Here we go. Don’t baby it.’ It was just a reminder for me that, ‘Hey, don’t go out there and get crazy. Just do what you do. Don’t baby it.’”

Bartlett led off the seventh. After nearly opening the game with an extra-base hit and then very nearly reaching on an infield single in the fourth, he smoked a ball to left, but right at left fielder Eric Patterson.

The next batter, Crawford, grounded out to second. Then Zobrist flew out to right field for the third out. It was a seven-pitch seventh for Braden.

21 up, 21 down.

In the eighth, Braden continued with the economical pitch count, getting Longoria to fly out to center and Peña to foul out to Kouzmanoff in foul territory on a combined six pitches.

Upton stepped to the plate and Braden quickly got ahead in the count, 0-2. Then came the moment that Braden knew this was his day.

“I threw a fastball on the inside part of the plate past him,” he said. “B.J. is a stud. The pitch, the location, the way it came out, his late swing … I threw it and I walked off the mound telling myself, ‘It’s a wrap.’”

And with that, Braden was three outs away from history. After receiving the pitch that struck out Upton, Powell pocketed the baseball.

“I have that ball,” Powell said. “That ball is in my house right now.”

‘Go, Grandma’

The day Braden was called up to the Majors in 2007, he called his grandmother and told her that she was retired.

“He told me that if I didn’t quit,” Peggy said, “he’d burn the motel down.”

So on the day after he made his big league debut, Braden had a U-Haul waiting at the motel to move everything out of her apartment.

From that point forward, every time Braden pitched at the Oakland Coliseum, Gran was there to watch him.

But in the top of the ninth inning on Mother’s Day in 2010, she would do something she had never done before. And she didn’t have time to ask for permission.

Her grandson had retired the first 24 Rays batters consecutively. The 25th batter he faced, Aybar, lined out softly to first base.

That’s when Peggy left her purse in her seat and started to make her way down from the family section and toward the field.

As she got about halfway to the front row, Navarro lined a ball to left. Braden hopped on the mound after his follow-through, fearing that history would be snatched away just before he could take hold of it.

“Eric Patterson was playing left field for the first time in his life,” he said. “Navarro hit that ball with some topspin -- a tough play, especially if it’s your first time out there. I can only imagine what he was feeling as that ball came toward him.”

Patterson initially broke in, but then backed up and moved to his left before reaching up and making the catch.

Peggy continued making her way down, and with just one out standing between her grandson and the history books, she went right past ballpark security and made a move she still can’t explain to this day.

“I just climbed onto the dugout,” she said. “I don’t know how I did it. I just did it.”

As a security guard near her looked on, he had no intention of stopping her, instead urging her on with two words:

“Go, Grandma!”

‘We got Mother’s Day back’

As Braden prepared to throw his first pitch to Gabe Kapler with two outs in the ninth inning, only 18 pitchers in the nearly 150-year history of Major League Baseball had thrown a perfect game, not yielding any baserunners of any kind.

With one more out, the little-known left-hander would take his place in that exclusive club, attaching his name to a masterpiece that represented one of the most improbable feats in the game’s history.

As the 12,228 fans in attendance at the Coliseum -- including several from Stockton who were sitting in Section 209 (209 is Stockton’s area code) on the first day of a special ticket promotion for when Braden started -- stood to their feet in anticipation, Braden went to work against Kapler.

By this point, the sun, which had been hidden for most of the day, was shining brightly.

Kapler worked the count to 3-1. If Braden’s next pitch was outside the strike zone and taken by Kapler, the perfect game bid would be over.

But Braden didn’t know the count.

“He thought it was 2-2,” Korach said. “The 2-1 pitch that he threw to Kapler, he thought it was called a strike.”

“He wanted to throw a changeup,” Powell said. “So he shook me when I put down the sign for a fastball. I knew it was 3-1, so I was like, we’re not gonna lose this perfect game on a ball here.”

Braden went with his catcher, as he had for nearly every pitch Powell had called that day.

On Braden's 109th pitch, he threw an 87 mph fastball -- he hadn't thrown a pitch over 89 mph the entire game. Kapler swung and hit it off the end of his bat toward shortstop. The ball had backspin, making it anything but a routine play.

Cliff Pennington moved to his left, got in front of the ball and waited a split second to get as true of a hop as he could. He gloved it cleanly, and now the 19th perfect game in Major League history was in his hands.

“Having the history that I have with Penny,” Braden said, “because we played against each other in college and came up through the Minors together, I knew what he was all about.

“As far as him getting to the ball and him fielding it cleanly, not a worry in the world. As far as his arm goes, this dude was a closer in college throwing 95 mph.”

All that remained was the throw. And Pennington had just one exhortation for himself in that moment.

“He said he just told himself to throw the ball down low to Barton at first base," Korach said. "He thought that if he threw it high, it might go over Barton’s head, but if he threw it low, Barton would scoop it.”

Korach had the call on KTRB radio.

“Two out, nobody on, ninth inning,” he said. “Bartlett is on deck. And Braden turns, he throws. It’s swung on and it’s a ground ball to short! Taken there, Pennington’s got it, he throws …”

The throw was perfect.

As was Braden, who thrust his left fist into the air before being mobbed by his teammates.

“A perfect game!” Korach exclaimed. “Dallas Braden has thrown a perfect game! The A’s have beaten Tampa Bay, 4-0! The kid from Stockton has done it for the A’s!”

In the middle of the chaotic celebration, Braden only had one thing on his mind: getting to his grandmother.

As soon as he emerged from the mob scene, Braden looked to where he knew Peggy was sitting in the stands. But she wasn’t there.

“I was just yelling, ‘Where’s my grandma?! Get my grandma down here!’” he remembers.

He then saw her being helped onto the field from atop the A’s dugout.

The two embraced and the tears began to flow.

“In that moment, I wanted me hugging her,” Braden said, “I wanted that to be the moment that we could both look back and remember that this is when …”

Braden paused, overwhelmed by emotion and trying to compose himself to continue. Seven seconds later, he spoke again, his voice trembling.

“ ... That this is when we got Mother’s Day back. This is when Mother’s Day was given back to us. And now we get to celebrate it again. We get to enjoy it again.

“This day gets to mean what it should have meant this entire time.”

Beyond zeroes on the scoreboard

Every Mother’s Day, Korach feels the heartache of losing his mother half a century ago. But now, that sadness does not dominate this day.

“When I saw Peggy go down to the field and she and Dallas embraced,” he said, “that was the single most emotional moment I’ve ever had as a broadcaster. Thinking of it still brings a smile to my face.

“When Dallas says he felt like he got Mother’s Day back, I feel the same way for myself. No doubt about it.”

Braden’s story has been an inspiration to many, particularly those who, like him, lost their mothers too soon or had a difficult childhood. But in the end, if you asked him to sum up that special and historic Mother's Day in 2010, it wouldn’t be about the fact that he threw a perfect game.

It would be about what made the perfect game so special, beyond the zeroes on the scoreboard.

“I am the living embodiment,” Braden said, “of what it means to be raised by powerful women.”