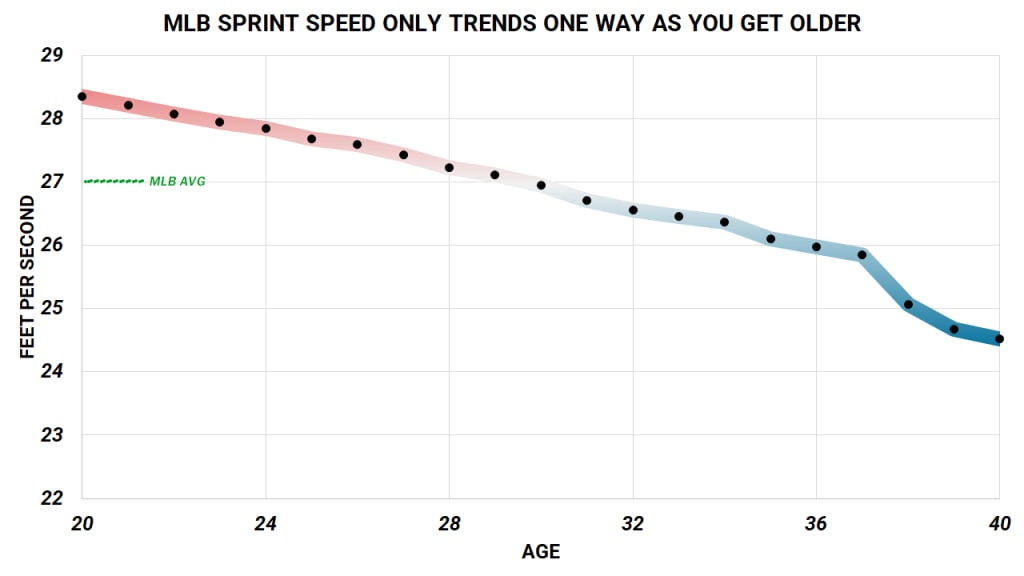

In baseball, as in life, there’s really only one certainty: You’re going to slow down, and eventually stop. Time remains undefeated.

If you’ve heard the phrase "aging curve," then you already know where we’re going here. Fastballs get slower, as do bats, as do feet. Aging defenders move to easier positions, and when fielders get younger and faster, defense gets better. It’s the rare case where the data and the eye test tend to match up perfectly. It happens to everyone, eventually. Older players get slower, and eventually get moved aside entirely.

It’s the one fact of baseball that applies to everyone. Except, it seems, to Byron Buxton and Trea Turner.

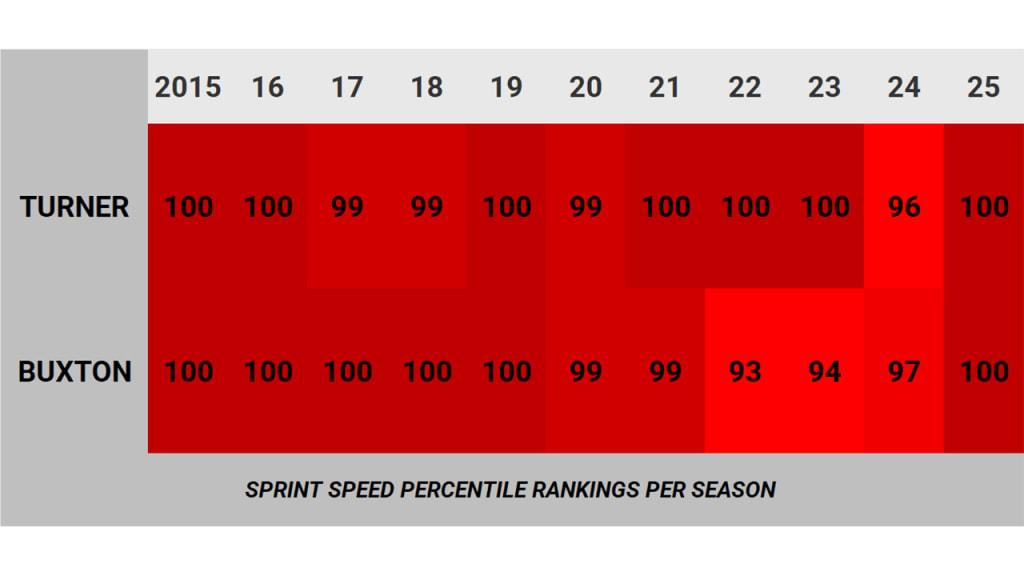

A decade ago, when Statcast first came online in 2015, Buxton (then in his age-21 season) and Turner (22) were the fastest men in baseball. Here in 2025, Buxton (now 31) and Turner (32) are still essentially tied with Bobby Witt Jr. for … being the fastest men in baseball. Take the entire Statcast Era together cumulatively, and Buxton and Turner are similarly tied with Witt for … the fastest men in baseball.

As the rest of the sport is doing this …

… Buxton and Turner, born six months apart from one another in 1993, are doing this:

This, while most of their peers have watched their speed head downward. Francisco Lindor, another 1993 baby, debuted in 2015 with 87th percentile speed. He just celebrated his 200th stolen base on his way to Cooperstown, but he’s now got slightly below-average speed (47th percentile). You could say the same for Mookie Betts, eight months senior to Turner, who also peaked with 90th percentile speed in 2015 and kept it for a number of years -- before a long-running slide has him as a slower-than-average 37th percentile this year.

Sometimes it’s because of injuries; look no further than Ronald Acuña Jr., a comparatively youthful 27 years old, who once had elite 97th-percentile speed but now lives in the 68th percentile, thanks in part to a pair of major knee surgeries. Sometimes there’s not a clear reason, as in the case of Bo Bichette, who's also 27 years old and has quickly fallen from excellent speed (83rd percentile as a rookie) to stunningly poor (22nd today). The way these things work, it’s not that surprising when a Gold Glove-winning center fielder in Marcell Ozuna (peak speed of 82nd percentile in 2015, at 24 years old) becomes one of the slowest players in the game (7th percentile, in 2025), a full-time designated hitter who no longer touches a glove.

It’s the way it’s supposed to work. It’s the way it almost always works. But for Turner, who turned 32 in June, and Buxton, who follows in December, it hasn’t quite happened that way – despite very different paths to this point.

What’s different about these two? The genetic lottery, or specific training methods, or all of it? We asked some of their teammates, coaches and trainers what makes them so special.

TREA TURNER

Turner is the most valuable baserunner in Statcast history, and it’s not even really close, piling up the most value both in taking bases and stealing them. The only time in his career he didn't rank in the 99th percentile or better in speed was last season, when he missed several weeks recovering from a hamstring injury – which sunk him only to the 96th percentile. This year, he’s back atop the leaderboard with Witt Jr. and Buxton.

“Obviously, he works his butt off offseason-wise and things like that,” said Philadelphia slugger Bryce Harper, “but I think genetically, he’s just a freak, you know? He’s shredded to the bone, too, so that helps.”

Harper was Turner’s teammate for parts of four seasons in Washington as well as the last three in Philadelphia – they shared a field in Turner’s very first game in 2015 as well his most recent game, No. 1,224, on Tuesday – and he may very well have seen more of Turner than any other player, so consider him a valuable source of truth here.

"Just the way he works and maintains is huge for him. He’s always trying to progress, too. Whether it’s doing stuff in the weight room or on the field or in the offseason, he never wants to slow down -- and, obviously, he hasn’t.”

(Harper, eight months older than Turner, never had that elite speed to begin with, but his own speed path is far more traditional, peaking at 80th percentile in 2019 [when he was 26] and declining to 39th percentile this year, as he’s moved from right field to first base. Or: the way you expect these things to go.)

“I think it's all of it, I really do,” said Phillies manager Rob Thomson. “Some guys are just freaks, and he's one of them -- and I mean that in a good way, obviously. He's just different than a lot of other people.”

Freak. There’s that word again – used lovingly, of course.

“It’s a little bit of everything, for sure, but definitely some genetics, obviously,” said Turner, who credited his mother’s side of the family for his speed, and we’re now 3-for-3 that he was just born with it, and so maybe that’s the answer right there.

If so, there’s a thought that maybe the truly elite speedsters should have their own, separate aging curve – that they’re not “normal” to begin with. There might be some truth to that, except that Turner, by his own words, wasn’t always this fast.

“I had to work on it. … Even when I was in high school, I wasn’t that fast," noted Turner, who failed to make the cut for several travel ball teams in his youth. "I got a little faster my senior year into college.”

“I just pay attention to my body a lot,” he continued. “I pay attention to the way I walk, I pay attention to how I’m running. It’s one thing to run fast, but it’s another to run fast and stay healthy and be in a good spot. I had the hamstring [injury] last year, which was probably more running form than anything, so I just try to pay attention to it quite a bit. And I think that’s what helped me quite a bit.”

BYRON BUXTON

While Turner's lower body has stayed relatively healthy, aside from 2024’s serious hamstring injury and a more mild one in 2017, Buxton’s litany of injuries sometimes feels endless. In his 11th season in the Majors, he’s been able to take 400 plate appearances in a season only one time, that coming back in 2017.

Even if we set aside the issues not directly related to running, the list is a lengthy one: Buxton missed two weeks in ‘17 with a groin strain, and more than a month in 2021 with a hip issue, and much of 2022 with hip and knee trouble, and was limited to DH duty entirely in 2023 with a hamstring strain around a pair of knee surgeries, then missed time in 2024 with more hip and knee issues.

The knee trouble in 2023 was so serious that the Twins openly worried it might be chronic, requiring constant monitoring. After all of that, he’s not just back to peak speed – he’s having what looks like a career season.

You might need incredible physical gifts simply to start off with elite speed, but to come back from all that requires a very different kind of dedication, and that’s exactly what the Minnesota staff focused on.

“Buck has been blessed in many ways with great ability,” said Twins manager Rocco Baldelli, who has been Buxton’s skipper for the last seven seasons, “but you don't get blessed with great work ethic and determination. That's totally different. There's physical gifts that God gave you that you can thank your parents for. He has an entire other set of strengths and really assets to all that he's accomplished, which is the fact that he shows up and the work ethic is incredible, and he has this desire to be great, and he doesn't let challenges get in his way; he kind of uses them to propel himself off of them.”

“He's dealt with as much as anybody in Major League Baseball has with injuries,” Baldelli continued. “But the only way you return to this level of performance and the only way you keep your body in a place that he's kept it is by putting in the effort every day. You have to be a through-the-roof kind of guy, determination-wise, to want this. You have to almost be obsessed in a lot of ways with that level of work. It's hard to take care of your body to that extent, and he does it. He continues to do it. It's not a 'sometimes' thing or a 'most of the time' thing. It's his life.”

It’s not just pure running speed, either. It’s what it becomes. While Turner has been the most valuable baserunner in Statcast tracking history, it’s actually Buxton who is tied with Corbin Carroll and Elly De La Cruz as the best baserunners of 2025. It’s Buxton who has been one of the truly elite defensive outfielders, going back and forth with Twins teammate Harrison Bader as the second-best outfielder on record since 2015 behind only Kevin Kiermaier, himself likely one of the all-time greats. There he is again in 2025, posting +4 Outs Above Average.

After all the injuries, he’s back to the same elite speed he – by the data, anyway – somehow never really seemed to lose, miraculously never sinking below the 93rd percentile in speed, which happened during a 2022 campaign when he dealt with knee pain all year long.

“Byron likes running,” noted Twins head trainer Nick Paparesta. “He loves running. He likes playing defense. Not that he doesn’t like to hit, but he likes all those other things more than he likes hitting.”

Paparesta joined the Twins with 28 years of training experience with the Guardians, Rays and A's, and he mentioned Coco Crisp and Carl Crawford as comparables.

“The year that he had to DH was really difficult for him, in that aspect of it,” continued Paparesta. “He does enjoy basically going out there to do what’s best to help his pitcher and his team. When that was taken away [and then he can play the outfield again], I think you get a little bit of the enjoyment back in that. With that enjoyment comes his desire to want to keep doing it at the elite level that he’s doing it at. He works very hard at it.”

Who stays this fast, this far into their careers?

It’s obviously natural talent. It’s obviously hard work. But what about the idea that if you can start at that elite range, then maybe you can keep it in a way that those without such a blessing cannot?

Here’s the problem with answering that question: It’s just so hard to find examples comparable to Turner and Buxton.

In the 11 years of tracking, we’ve seen a 30-or-older player hit the elite level of 30 ft/sec in a full season just three times. Two of them are by Turner, adding 2023 to this year. The other is Buxton, this year. You can see the problem.

Setting aside age for a moment, only 40 players since 2015 have hit the elite level of 30 ft/sec at all, and Turner and Buxton alone are responsible for about 20% of those seasons. It’s difficult to test, though, because so many of those players popped up for a brief Major League taste but didn't have the bat to stick there (like short-time Cardinal Ben DeLuzio), or are still in their mid-20s and haven’t yet fully written their stories (Witt Jr., De La Cruz, Carroll, etc.)

That being the case, comps are hard to come by. We identified only 10 other players since 2015 who had at least five qualified seasons of running, with at least one being 30 ft/sec or better, and played (or are playing) at least through their age-30 season. Four of them – Bader, Garrett Hampson, Tyler O’Neill and Billy Hamilton – lost that elite speed by 31, but still at least maintained above-average fleetness. One, Buxton’s former teammate Manuel Margot, followed a more Ozuna-like path to lead-footedness.

A handful of others – Tim Locastro, Jorge Mateo, Adam Engel, Eli White and Myles Straw – have continued to flash top-end speed into their early 30s, though of course with a small fraction of the playing time Turner and Buxton have enjoyed. It’s possible that other, non-qualified players – think Terrence Gore or Dairon Blanco types – may have been able to maintain that speed had they possessed other skills to warrant such playing time. But they don’t, and that’s the point. It's one thing to keep the speed as Turner and Buxton have; it's another to do it over such a long period of time, playing at such a high all-around level. (Turner is 10th in WAR since 2015; Buxton, limited by injuries, is 42nd.)

In both cases, it’s not just about having the elite speed, or working to maintain it. It’s understanding at 31 what you may not have at 21.

“I say a lot that I’ve got to keep up with the 20-year-olds, because on that list, there are very few guys over 30 in the top 10,” said Turner. “But I kind of have the right body for it, I don’t have a lot of weight on me. So I try to stay in the same weight category: I don’t want to gain a bunch of weight and have that change my game, or vice versa, lose a bunch of weight. So I feel like I’ve got a good balance.

“No 20- or 21-year-old guy knows that they have to do these things,” echoed Baldelli. “Once [Buxton] realized what he needed to do to stay in this game and play it at a high level, he just put himself to it and does it, and he brings it every day. It's hard to look like him, play like him, and honestly, get back from what he's gotten back from at 30-something years old. It's a very difficult thing to do. Most people can't do that. They're not capable. Not because they're not physically capable, but because they're not able to dedicate themselves the way that Buck has. You like seeing a guy that puts in the work to get it on the other end.”

It’s work. It’s genetics. It’s all of it. What it is is unusual, really. It’s elite speed, despite age and injury. It’s bucking the trend to which every other player inevitably succumbs. Everyone, that is, except them -- so far.

MLB.com's Paul Casella and Matthew Leach contributed to the reporting of this article.