This story was excerpted from the Cubs Beat newsletter. To read the full newsletter, click here. And subscribe to get it regularly in your inbox.

Of all the All-Star nods that no one saw coming in Spring Training, Matthew Boyd has a case for most improbable.

A first-time All-Star in his age-34 season, Boyd is plenty deserving of the recognition. His 2.34 ERA is fifth best among qualified starting pitchers, trailing only Paul Skenes, Garrett Crochet, Tarik Skubal and Jacob deGrom -- some of the game’s truly elite arms. Boyd, a left-hander, has anchored the first-place Cubs amid a deluge of pitching injuries, providing both stability and excellence.

It’s the culmination of a long journey for the 11-year veteran. Two major surgeries -- first for a torn flexor tendon in 2021, then Tommy John surgery in ‘23 -- granted Boyd plenty of time to think about the type of pitcher he sought to become.

“In rehab, the big thing for me was, who am I?” Boyd told MLB.com earlier this month at Yankee Stadium, a day after tossing eight shutout innings. “Let’s go be the most comfortable version of me and see where the metrics play out. Little tweaks. I’m not going to chase something at the risk of it ruining something else.”

That’s a seasoned perspective, and one that took Boyd a while to learn. Pitchers have more data at their fingertips than ever before. At times, it can be overwhelming: How do you know which metrics to prioritize?

“Early on, I think really in the middle of my career, when all the metrics became so readily available, we all started chasing different things,” Boyd said. “In that sense, I lost the identity of who I was.”

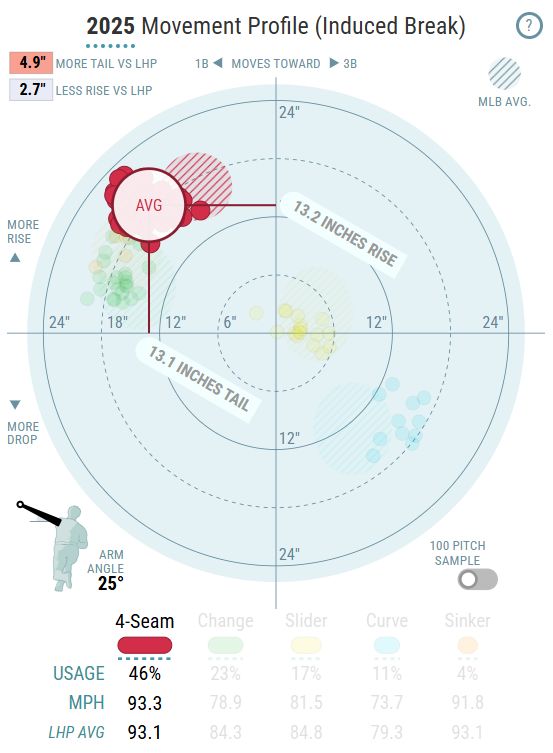

These days, Boyd’s primary weapon is his four-seam fastball. He throws from a low three-quarters arm slot -- with a 24° arm angle -- creating outlier horizontal movement on the pitch. With an average of 13.1 inches of horizontal break, Boyd’s four-seamer has 5.0 more inches of horizontal movement than comparable pitches. Despite average velocity (93.3 mph), the opposition is hitting just .240 against Boyd’s fastball; his +12 Fastball Run Value is in the 95th percentile.

The pitch is successful in part because of its approach angle, or the angle at which the baseball arrives at the plate. Boyd, who is 6-foot-3, throws from a low release point, just 5 1/2 feet above the ground. Combined, his low slot and low release point create a “flat” approach angle; the pitch comes to the plate at an angle that “jumps” on hitters. It’s one they’re less accustomed to seeing, and in pitching, being unique often creates an advantage.

Boyd knows this makes him successful. It just took him some time to realize it.

“I didn’t know about the approach angle, but by chasing vert and some other things, I lost my approach angle because I was climbing my slot,” Boyd said.

When Boyd mentions chasing “vert,” he’s talking about induced vertical break (IVB), which attempts to quantify the vertical movement a pitcher creates by the way he spins the baseball, stripping gravity from the equation. Fastballs with a lot of IVB (more than 20 inches is elite) will have a “rising” effect, often causing the hitter to swing underneath the pitch. Pitchers who throw from a higher, more over-the-top arm slot are more likely to generate the backspin that’s required to attain rise.

It’s nice when the numbers match a story. We now have six seasons of Statcast arm angle data, dating back to 2020. In that period, we can clearly see when Boyd raised his slot to chase IVB, as well as when he stopped.

In 2021, Boyd’s arm angle crept up to 31 degrees. The shape of his four-seamer changed, too, reaching an average of 15.2 inches of IVB -- the most vertical movement Boyd’s four-seamer has averaged in a single season since 2018.

“Justin Verlander spins a 20-inch vert fastball, I want to do that!” Boyd remembered thinking. “But that’s what makes him who he is. This made me, me. I still struck out a lot of guys throwing 91 right down the middle. And it was not because of my vert, but because of my slot. And there’s no one to blame for that. We’re just learning more and more.”

And that’s key here, too, because as Boyd’s career has progressed, he’s learned how to use data to maximize his skillset -- especially that approach angle.

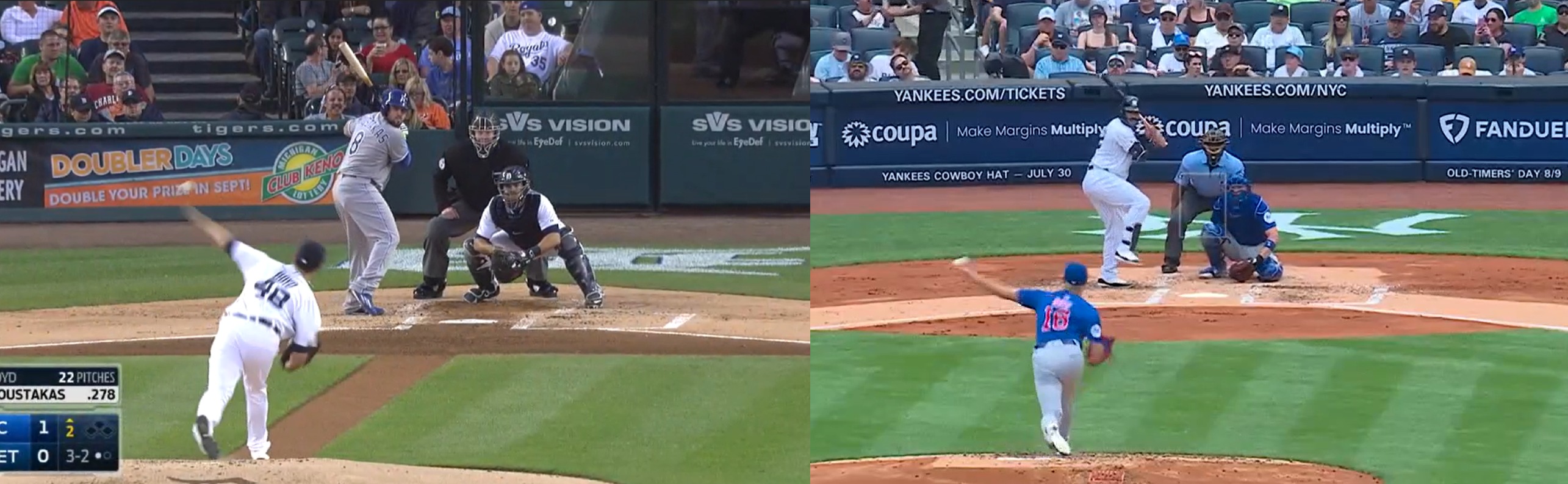

For one, Boyd has dropped his release point by over 8 inches since his debut season in 2015. He’s learned to lean into what he calls the “funkiness” in his delivery. It’s pretty easy to see the difference here, in this side-by-side of his release point in 2015 (left) and 2025 (right), by looking at the slope of his left shoulder.

There are other ways to unlock the approach angle bonus, too. In 2015, MLB Pipeline wrote in Boyd’s scouting report that “he does a good job of keeping [his fastball] down in the zone.” And, by all accounts, he did. The only problem is that wasn’t necessarily the right way to go about things. Flat fastballs -- like the one that Boyd wields -- are best when thrown up in the zone, maximizing their “rising” effect.

“People would say that you have a flat fastball, and they would tell me it doesn’t play,” Boyd said. “But it didn’t play down. They didn’t understand that, if you throw it up, it’s going to play even better. I tried to throw it up as my big league career went on and it was like, ‘OK, you know, I actually have a lot of success up there.’ It’s definitely been an evolution.”

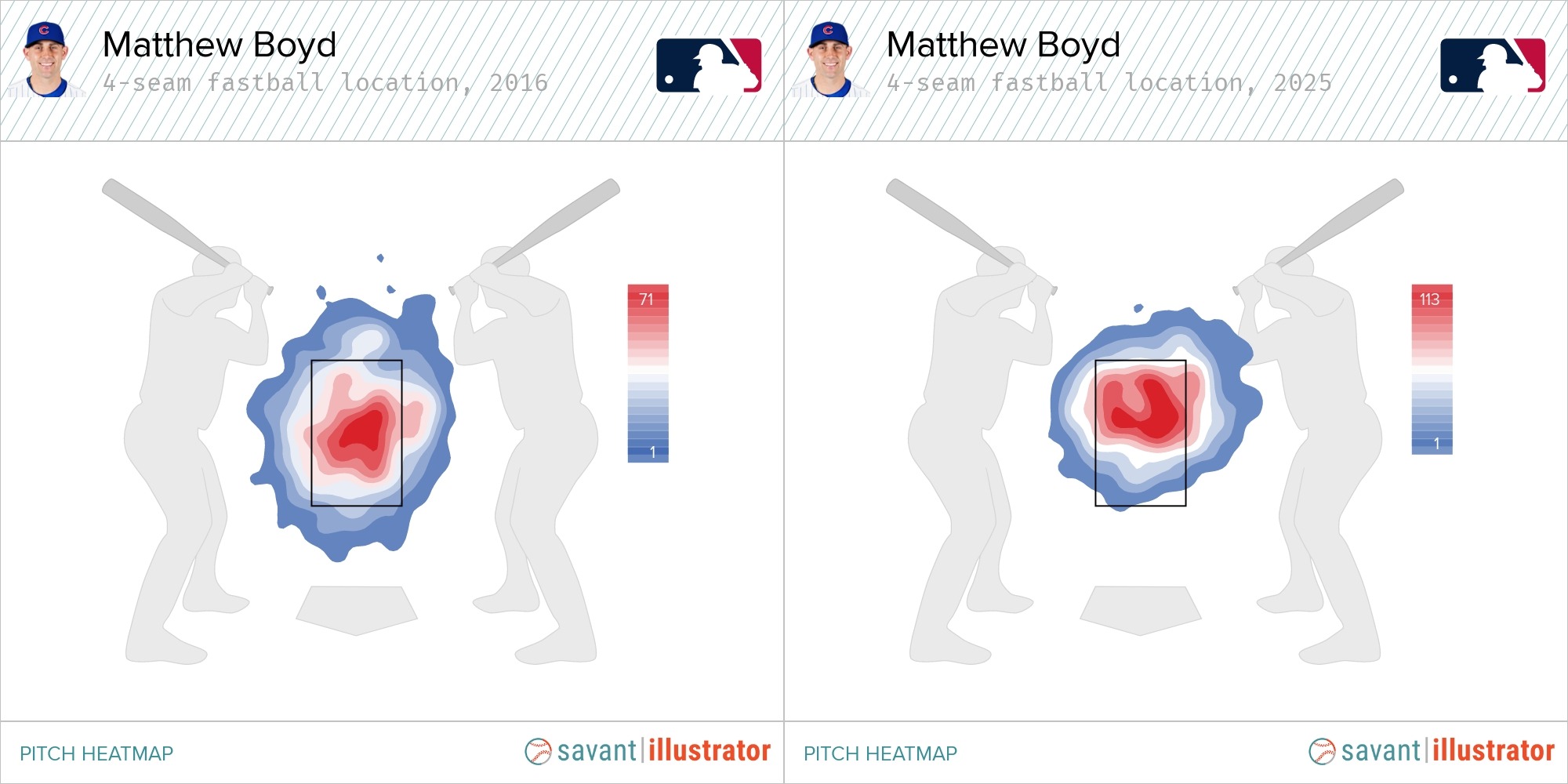

The heat maps below show the location of Boyd’s four-seam fastballs in 2016 -- his first full season in the Majors -- and the same subset of pitches in 2025. He’s changed his intent.

And it’s paid off. Batters are hitting .200 with a 20.6% whiff rate against Boyd’s four-seamer when it’s located in the upper third of the strike zone. When it’s in the lower third of the strike zone, batters are hitting .296 with a 2.5% whiff rate.

Even though his velocity is up this year -- Boyd eclipsed 96.0 mph twice in his last start, matching his previous total of 96+ mph pitches in his entire career -- that’s not what makes his fastball so good. He knows that now.

“Because of my slot, because I hide it, because of a little bit of a funk in my delivery, it probably plays up,” Boyd said. “I don’t chase the metrics as much, knowing that my approach angle is what’s going to help make it unique.”

He found something that works for him, rather than seeking something that works for others. That’s really all Boyd has ever done, dating back to the origin of his arm slot. As a 16-year-old, Boyd played on his dad’s summer team, shuffling back and forth between first base and pitcher. One day, in warmups, he didn’t feel great on the mound.

“I remember saying, ‘I’m going to throw like a first baseman on the mound,’ and I just shortened up,” Boyd said. “I started throwing more strikes than I ever threw before. My changeup and curveball were right where I wanted them. My Dad asked me, ‘Buddy, why are you doing that?’ I said, ‘Well, it feels really good.’ He’s like, ‘OK, well keep going with it.’ And that was it. Simple as that.”

All these years later, he’s back to following the same mindset, true to himself.