As a rainstorm soaked the city of Passaic, N.J., on May 3, 1933, six boys living at an orphanage had one concern: What is all this water doing to our baseball field?

Sometime after 7 p.m., they convinced the matron at the Passaic Home and Orphan Asylum, a Mrs. Emma McCrea, to let them go outside to inspect their field. What they found was a muddy mess – but what they spotted nearby was much worse. Not far from the field was an embankment upon which the Erie Railroad commuter train ran, and the dirt beneath the tracks had been washed away in the storm, leaving a ditch some 10 feet deep.

Just then, a whistle signaled an approaching train, with more than 400 passengers on their way home from work. The six boys – Rudolph Borshe, 15; Jake Melnizek, 15; Douglas Fleming, 14; John Murdock, 11; and brothers Frank and Mike Mazzola, 13 and 11 – ran up onto the tracks into the path of the train and removed their raincoats, waving them furiously to get the engineer’s attention. He brought the train to a halt, then emerged from the locomotive to admonish the boys.

“At first the engineer got out and was yelling and screaming at us,” Murdock recalled in an interview in The Record, a northern New Jersey newspaper, in 2005. “But when he saw the big ditch underneath the tracks, he got down on his knees and thanked us.”

To Borshe, it was what needed to be done.

“We all thought about it, so we just started and ran down the track and waved our raincoats and the train stopped,” he told a New York Times reporter in 1933. “The engineer was pretty mad until we told him about the washout.”

Fleming put it succinctly, according to The Times: “When you see a hole in the track and the train is coming you’ve got to stop the train.”

Their quick thinking had prevented the train from crashing into the ditch, and they were quickly lauded for averting a disaster and saving lives. When asked what they wanted in return for their heroic actions, one request topped the list: Would you let Babe Ruth know what we did?

The boys knew the Babe’s story of growing up in an orphanage, the St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys in Baltimore, and thought – accurately, as it turned out – that this connection might resonate with their hero. It was the Great Depression, and though the boys lived in an orphanage, they weren’t necessarily without any parents. Murdock’s mother had died, but his father struggled with providing for six children – not that dissimilar from Ruth, who had been sent to St. Mary’s by a father who struggled to keep the “incorrigible” youth in line.

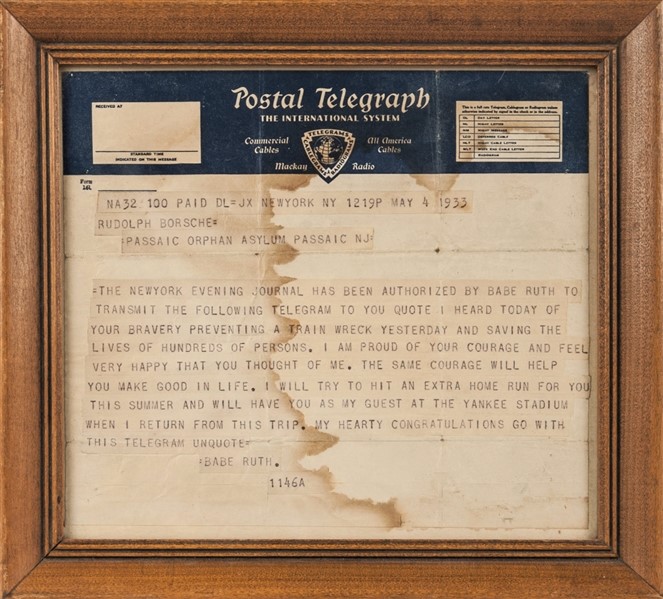

When word reached Ruth in Detroit, where the Yankees were playing, he responded in a telegram with his congratulations and promising that he’d invite them to Yankee Stadium when the team returned from its road trip.

“I heard today of your bravery preventing a train wreck yesterday and saving the lives of hundreds of persons,” the telegram read. “I am proud of your courage and feel very happy that you thought of me. The same courage will help you make good in life. I will try to hit an extra home run for you this summer and will have you as my guest at the Yankee Stadium when I return from this trip. My hearty congratulations go with this telegram.”

He also sent six autographed baseballs through the mail and promised to visit the boys at the orphanage.

“Say, there must be something in this baseball business, after all, something more than money,” he was quoted as saying in The Herald News of Passaic on May 4, 1933. “Imagine those boys in the midst of all the excitement asking that I be told about their bravery. It’s a kick, boy, a big kick!”

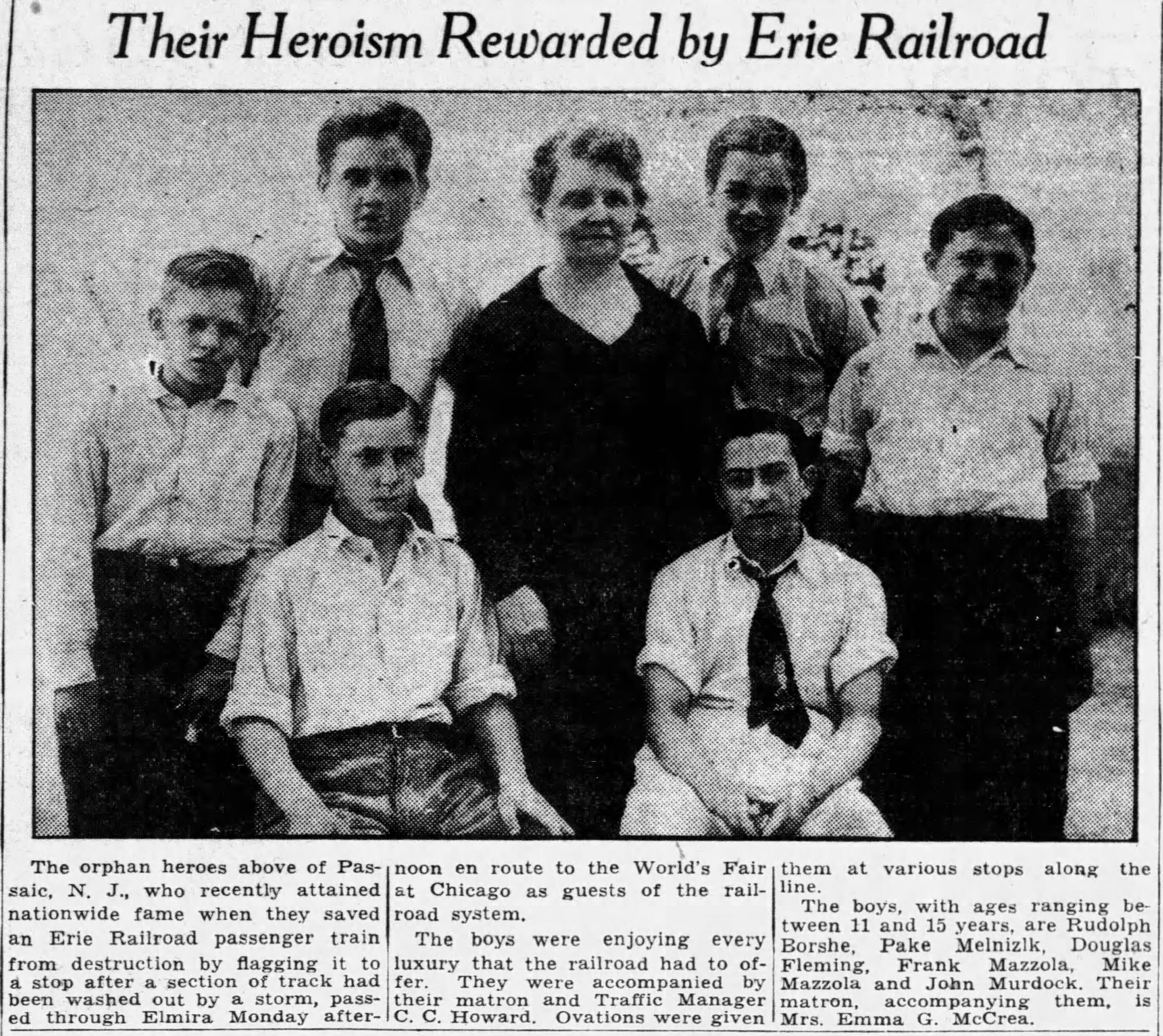

Wire services picked up the story and it ran in newspapers across the country, making the front page of The New York Times and papers from Florida to California. Over the next few months, the boys received medals from the city of Passaic, Lionel train sets from the Erie Railroad, wrist watches from a Newark department store, and a trip – by train, of course – for all six to attend the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago in June. Congratulations in the form of telegrams came in from both of New Jersey’s senators in Washington and Boston Braves third baseman Fritz Knothe, a graduate of Passaic High School.

There was one perk that they had to decline: an offer from vaudeville producers to appear on stage, with “a large sum” as compensation, according to The Times. Mrs. McCrea put her foot down on that one.

But the biggest prize was recognition from the Babe, which culminated in his visit to the orphanage on May 19, 1933, and their attendance at the Yankees’ game vs. the St. Louis Browns the next afternoon.

At 38, Ruth was seven months removed from hitting his famed called shot in the 1932 World Series – but also in his penultimate season with the Yankees, playing on unsteady legs. When he promised to hit a homer for the orphans, he had 657 regular-season round trippers behind him and just 57 remaining. His most recent clout had come on April 30, four days before the boys’ heroic actions; he wouldn’t hit his next until May 23, three days after they were his guests at Yankee Stadium.

Just after 11 on a warm Friday morning, Ruth arrived in Passaic somewhat unannounced (a call to the orphanage alerted the staff that he was on his way) while the boys were at school about half a mile away. The Bambino chatted with Mrs. McCrea while the boys were summoned from their classes.

When they arrived, he greeted them with a hearty, “Hello, fellows!” and distributed the gifts he had brought: neckties with his name and likeness for everyone in the orphanage, blue caps with “Babe Ruth” stitched across the front, and six autographed bats that drew cheers when presented to the young heroes.

Ruth and his hosts then went outside, where he gave them batting tips and a pitching demonstration before they took him to the scene of their good deed.

“They brought him to the railroad track where the washout had occurred,” The Herald News reported. “Then they got their raincoats and went through the entire incident while Babe looked on and applauded.”

After Babe and the boys posed for some photos, they asked him to stay for lunch, but he had to be back at Yankee Stadium for a game scheduled for 3:15 p.m. His visit lasted about an hour, and before getting back into his car with his entourage of reporters, he invited the youngsters to the game the next day.

“I’ll see you before the game,” he said. “And I promise to hit a home run especially for you. It will be one of the deepest regrets of my life if I don’t send one into the stands for this gang.”

The next day, a Saturday, the six boys and 20 of their fellow residents at the orphanage boarded a bus for New York City. The first stop was Gimbels department store for lunch and new suits for the favored six.

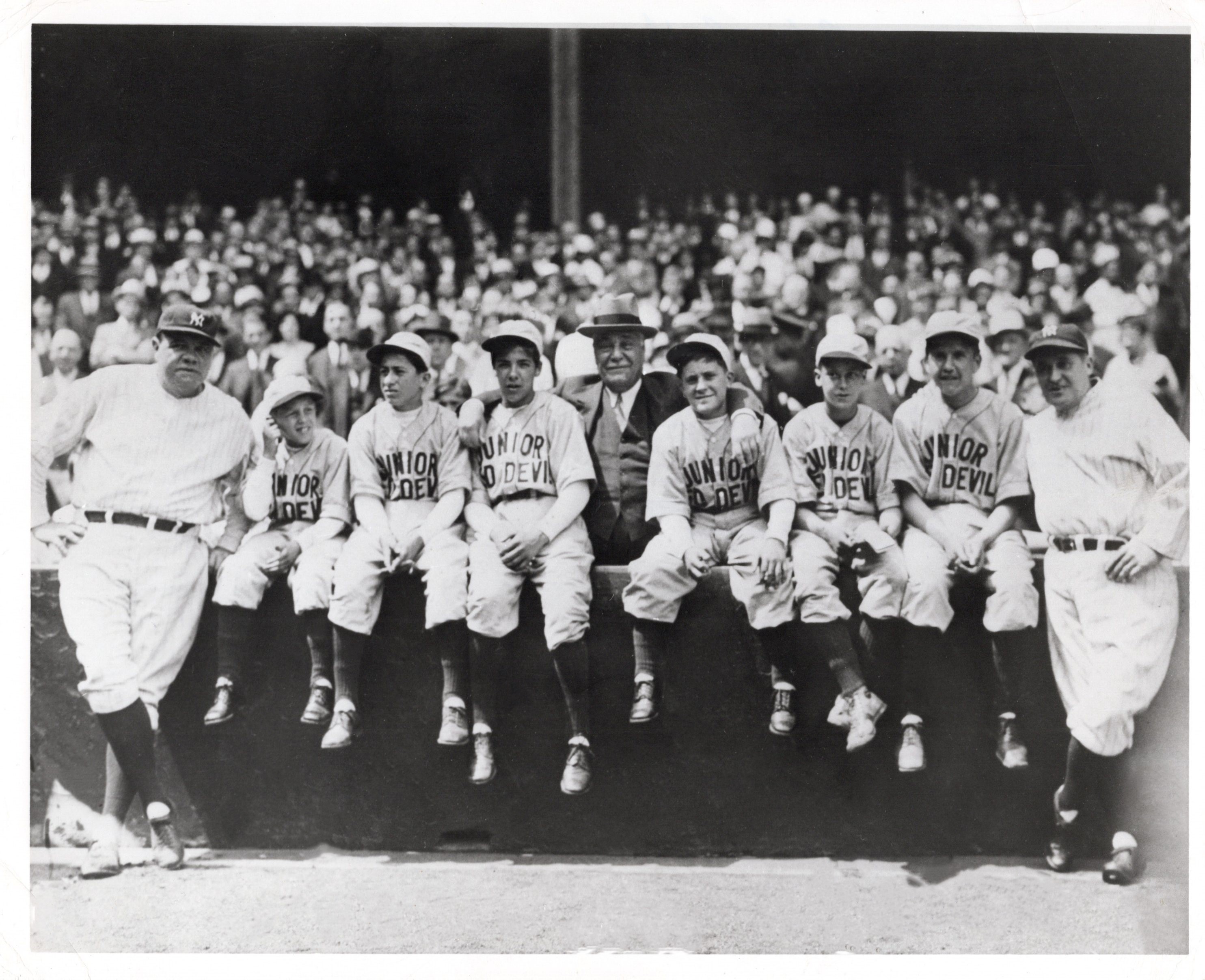

At the stadium, the orphanage baseball team – the six heroes among them – emerged wearing new uniforms provided by famed columnist Walter Winchell. The gray togs featured the team name – Junior Red Devils – in red lettering across the front. Cheered by the crowd of 25,000, the young ballplayers were invited onto the field, where they scooped grounders and settled under fly balls hit by none other than Lou Gehrig and Ruth.

Yankees owner Col. Jacob Ruppert welcomed them to his box behind the third-base dugout, where he posed for photos and newsreel footage with the six guests of honor, along with Ruth and manager Joe McCarthy. Ruppert supplied them with “as much popcorn and peanuts as they could hold, and … many bottles of ‘pop,’” according to The Herald News. It was the first big league game for most of them, the paper reported.

Despite Ruth’s promise of a home run, there was no Hollywood moment on this afternoon. “The first time at bat,” The Herald News wrote, “he caught one ‘on the nose’ and the crowd jumped up with a roar as it headed for the right field stands. But it dropped just short of the fence and the St. Louis fielder took it for a putout.” Ruth went 1-for-3 with a walk, Tony Lazzeri scored both runs and homered in the ninth, and the Yankees fell, 4-2.

After their trip to Chicago a little over a month later, the boys faded from the headlines. Soon they went their separate ways, losing touch with one another, and all are believed to have passed away. The youngest of them would be about 103 years old this year.

Two years after their notoriety, Murdock was sent to live with an older brother in New Rochelle, N.Y. He eventually enlisted in the Navy, where he met his wife, Lois, in Chicago. They married and had a family, settling in northern New Jersey, about 15 miles from where Murdock once stood on the tracks and helped stop a train.

He kept that autographed baseball all his life, showing it to the reporter who visited his home in 2005, five years before he died at 88. But he never got back to Yankee Stadium. The only game John Murdock saw there was the one to which he was invited by Babe Ruth.

Thanks to Passaic historian Mark S. Auerbach for photos and guidance.